Design

Before getting to work on my folk dress, it was necessary to understand the historical folk dress and decide how to adapt it. Luckily, I have conducted quite a bit of research on Ukrainian folk dress over the years, so I knew what components I needed to address for this project upfront. There were a lot of considerations that were included in this process, however, so this page will be devoted to laying out my larger ideas for the dress as well as how I designed my embroidery patterns.

The page before this provides more context and background information about Ukrainian folk dress for those new to Ukrainian folk textiles. The pages after this one will extensively cover the various crafting that I have done to pull together my folk dress; I recommend checking these pages out for more in-depth information about the individual components. For now, this page will focus on how I approached my dress design as well as my embroidery patterns.

Sniatyn Dress Components

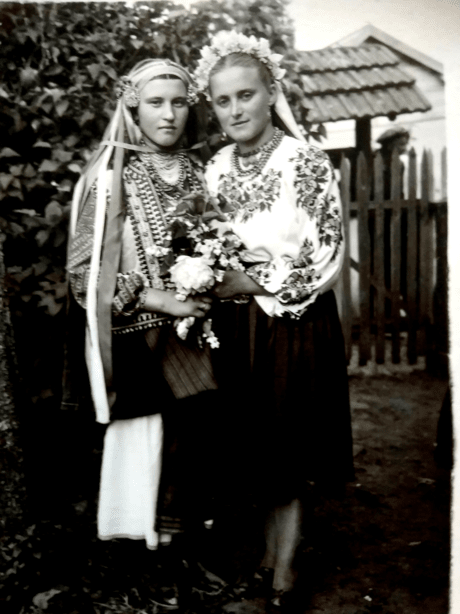

The historical Sniatyn folk dress has several components that differ from dress to dress. You would be hard-pressed to find two dresses from Sniatyn that are exactly the same; each dress consists of unique patterns and details that are meant specifically for the wearer. However, the foundational components of the historical folk dress are actually pretty straightforward. Here is a quick breakdown of the different components of a late 19th-century Sniatyn folk dress:

-

Sorochka (сорочка): a chemise made of white linen fabric, typically embroidered on the sleeves and cuffs, though sometimes embroidery is also added around the collar and hem.

-

Opynka (опинка): a heavy wrap skirt made of handwoven woolen fabric that is either red or black and is wrapped over the sorochka.

-

Okryyka (окрийка): a handwoven woolen belt that has geometric patterns, is typically dark red, and is wrapped over the opynka to hold it in place.

-

Keptar (кептар): a vest made of sheepskin that is heavily decorated with embroidery and other decorations, though it’s not a required component of the folk dress.

-

Coral-Bead Necklace (коралове намисто): a multistrand necklace made of coral beads (or artificial copies) worn to signify family wealth.

-

Silyanka (силянка): a bead necklace with bright geometric or floral patterns that is worn around the neck or as a headband.

-

Headdress: assorted crowds, headbands, and caps were used to decorate women’s heads for festivals/etc., though these decorations were not compulsory for unmarried girls/women.

-

Other necklaces and jewelry were often also worn to complement the silyanky and coral-bead necklaces; more information may be found on the Silyanka and Accessories pages.

The complete late 19th-century Sniatyn folk dress, then, consists of a chemise, wrap skirt, belt, optional vest, and an abundance of jewelry. Together, these components create a relatively uniform silhouette in which the rich embroidery and accessories act as the most compelling part of the aesthetic. This is the basic structure of the folk dress up to today. Some things have needed to change, such as the inclusion of more modern skirts with the death of Sniatyn weaving heritage. Yet the core components and silhouette remain in some form or another.

These different components are meant to be color-coordinated, with embroidery being the deciding factor. Once the embroidery pattern is set, the color of the opynka and belt may then be chosen to complement the embroidery. The dress is designed to draw attention to the rich embroidery and pile of necklaces.

Of course, please note that women rarely did all of this on their own. While embroidery has long been the common pastime of Ukrainian women, the weaving for the sorochka, opynka, and belt would have been fulfilled by local weavers. It was also common for girls to inherit their mother’s and grandmother’s older clothing; the wedding sorochka and coral-bead necklaces, for example, were often heirlooms within the family and would be reused for a couple of generations. No one person was expected to do everything on their own; instead, pulling together a complete folk dress was a family and even community effort.

Designing my Folk Dress

When designing my own design for the dress, I considered a few different factors that would contribute to the quality and feasibility of my project.

First, I wanted to follow the original design of the folk dress. This meant not just focusing on the embroidery, but also considering the historical dress as a whole. The silhouette of the Sniatyn dress is actually quite distinctive, so it was something that I wanted to create for myself. Chasing the silhouette then led me to understand the individual components of the folk dress more deeply, beyond just the embroidery. But I also wanted to experience the role of embroidery within the wider context of the dress; it was not until I was researching the opynka, for example, that I realized just how much of the folk dress was coordinated to enhance the embroidery. As an avid embroiderer, I find it fascinating to see just how central a role embroidery plays when designing the fuller folk dress. It placed the importance of embroidery in context to an extent that I never considered. There were so many little considerations in the designs, and going through this process for myself has been the best way to learn these details. Deciding to look into the other components of the folk dress has definitely given me a deeper appreciation of the overall harmony in the historical dress’s design. So, following the original form has been beneficial to my understanding of the full folk dress.

Second, it was necessary to consider my own budget, available time, and skillset within my own design. Again, I am a student and worker, so I have crafted my folk dress with a tight budget and limited time. Financially speaking, this meant that I could not always afford the best alternatives for my folk dress. Commissioning a weaver to weave my opynka, for example, was out of the question due to my limited budget. I also had to be careful in how I spent my time; spending a lot of time acquiring new skills, such as crafting a keptar, was also out of the question. I needed to focus on the components of the dress that I already had the necessary skills for, primarily embroidering and sewing. Deciding which components of the dress to include and craft myself was largely based on whether I could afford it and whether I had the time needed for skill acquisition and crafting. In the end, some parts of the folk dress had to be left out (the keptar), some were store-bought to save time (my coral necklaces and belt), and affordable alternatives had to be seriously considered (the fabric for my opynka). I have granted myself leniency with these changes with the understanding that I don’t have access to every possible option for my folk dress. I still take pride in having managed this careful balance with my own resources, which ultimately made crafting my folk dress possible in the first place.

Third, I wanted to craft something that would not sit collecting dust for most of the year. If I am spending my resources and time crafting something, then I actually do want it to be usable in a variety of situations. For me, this meant modernizing the basic components of the folk dress – the sorochka and opynka – so that I could wear them separately on a variety of occasions. Most importantly, this has meant that I replaced the sorochka with a vyshyvanka, which is shorter than the historical sorochka. Since the vyshyvanka is shorter, it can be worn with jeans for more efficient outfits and packed more easily when traveling. At least for me, wearing jeans and a vyshyvanka is easier to accomplish when traveling to events. I can wear it in a wide variety of contexts, without having to worry about the full folk dress every time. I want to be able to wear my embroidery whenever I want, and a vyshyvanka is an easier choice to accomplish this goal. Similarly, I made my opynka into a wrap skirt with a button partially so that I could wear the skirt independently, without the belt. I really try to make my crafting projects as useful as possible, so allowing these components of my folk dress to be worn separately and in a variety of contexts has been an important personal consideration.

With all of these factors in mind, the following is a list of the components of my own folk dress:

-

Vyshyvanka, in place of the sorochka – hand-crafted

-

Opynka, with alternative fabric – hand-crafted

-

Okryyka – purchased from other crafter

-

Coral-bead necklace – purchased from other crafters

-

Silyanka – hand-crafted

-

Headdress – purchased from other crafters

More specific information about the different components of my dress can be found within the next pages of this section. For the remainder of this page, I will spend some time discussing how I designed the embroidery for my vyshyvanka.

Sniatyn Embroidery Patterns

Designing my embroidery patterns was a bit more of a complex process. While practical considerations made the overall process of designing my dress fairly straightforward, the embroidery patterns for my Sniatyn-based dress did not have such clearcut boundaries and required more reflection and personal choices. I decided to use this page to go over my design process for my embroidery.

Initial Considerations

Historical folk dress in Sniatyn has some guidelines to follow, though they are not extensive. One guideline is that women’s shirts should absolutely have embroidery on the shoulders (shoulder insets). Most women’s shirts also have embroidery on the cuffs. Sometimes embroidery is also added around the collar, but this is reserved for wedding shirts, as the abundance of necklaces means that this embroidery would get covered up regardless. A lot of surviving embroidered shirts from Sniatyn also include embroidery that runs between the shoulder inset and cuffs; these richer shirts are preferred for weddings and other important events. Beyond the need for shoulder insets and using embroidery patterns from Sniatyn, I had limited guidance on how to design my embroidery and a lot of choices ahead of me.

Within the historical Ukrainian context, embroidery has generally been used for a few reasons: self-expression, aesthetics, protection, and manifesting the best intentions for events (weddings, etc.). These intentions for the embroidery give a few more guidelines for how I should design my embroidery. First, I knew that I wanted to have a vyshyvanka to wear in my everyday life and for festivals. This meant that I could skip the embroidery between the shoulder insets and cuffs if needed, since my vyshyvanka was not meant for formal or significant occasions. This stipulation was very helpful considering my limited time frame. Second, I found it important to practice self-expression with my design, so I knew I would only be embroidering patterns that I find aesthetically pleasing. I’m not very fond of all redwork, and I wanted to use more diverse patterns that showed off all the different colors and designs used historically in Sniatyn embroidery. When looking through patterns, I looked for ones that incorporated various geometric elements and colors, while still maintaining some cohesion found in the historical sleeves. Protection and intentions for a happy future are also important to me, of course, but these come more into play during the actual embroidering process than the design process, so we’ll discuss those later.

My final vyshyvanka for this project would include the shoulder insets and cuffs. Before getting into my design, it would be helpful to familiarize the reader with the different techniques and patterns used in Sniatyn embroidery.

Common Stitches in Sniatyn

The embroidery techniques used in Sniatyn folk embroidery are pretty diverse. While this is definitely not an exhaustive list, here are a few of the stitch types used in Sniatyn embroidery:

Cross stitch: Cross stitch is certainly the most recognizable stitch type in this list, as it is commonly used throughout the West and in various forms elsewhere (Palestinian tatreez, for example, includes cross stitch). This technique consists of making several x’s on the fabric in order to form a pattern. Cross stitch is usually used for geometric and floral patterns in Ukrainian embroidery. It is an important part of the shoulder insets in the Sniatyn folk dress.

Flat stitch: A variety of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal flat stitches are also used in Sniatyn embroidery. In simpler terms, this is a counted satin stitch, meaning that the stitch is a designated length based on the number of fabric threads that it can span. In most of Western Ukraine, flat stitches cross over 3 or 5 threads in the fabric; Pokuttia is a bit odd, as it typically spans 4 threads. This is to ensure that the threads are snug against the fabric. Flat stitches are used in a variety of ways throughout the entire Sniatyn sleeve.

Nyz’: This is another type of counted satin stitch, but it is designed in such a way that each side of the fabric will have a unique pattern. This technique is often found on the cuffs of Sniatyn shirts, using either red or black (though other regions may only use it for black). Nyz’ on the cuffs is typically worked vertically in the Sniatyn region.

Curly stitches: In addition to cross stitch, a number of “curly stitches” may also be employed in decorating the sleeves of the Sniatyn folk dress. These stitches are more commonly found between the shoulder inset and cuff. They may be worked in a variety of colors and add texture to the sleeve. The linked video covers some of the most popular curly stitches in the Sniatyn region.

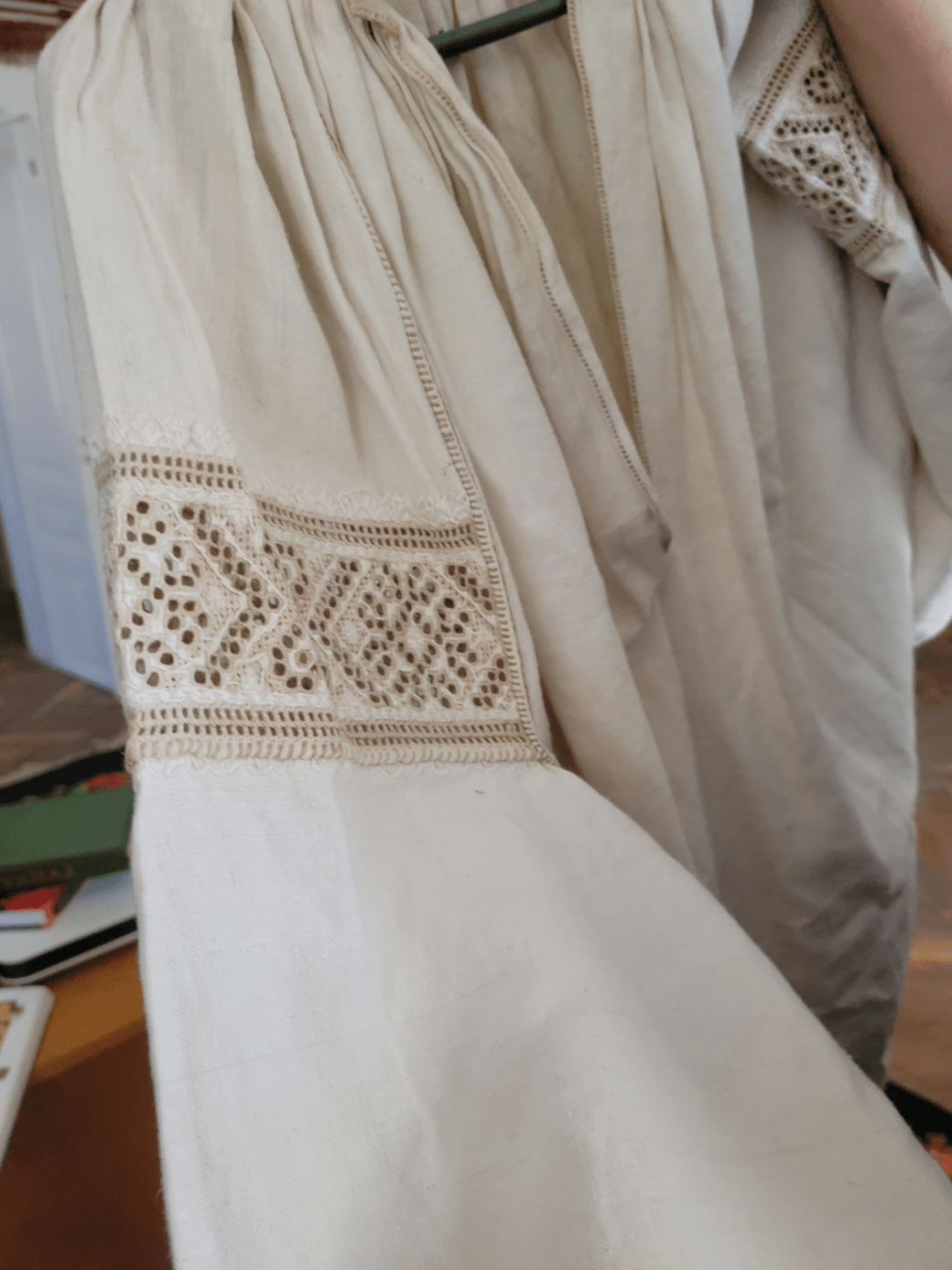

Openwork: For Sniatyn embroidery, openwork is synonymous with whitework. This technique consists of eyelets and other forms of bordering small parts of the fabric, cutting it out, and filling it with ornamentation. The openwork is then surrounded by white flat stitches (whitework). Openwork embroidered in white gives a lacey aesthetic to the fabric. This technique is used on the shoulder inset. It may then be bordered by cross stitch or flat stitches in other colors to frame the whitework. The linked webpage includes several photos of Sniatyn openwork.

Shoulder Inset Patterns

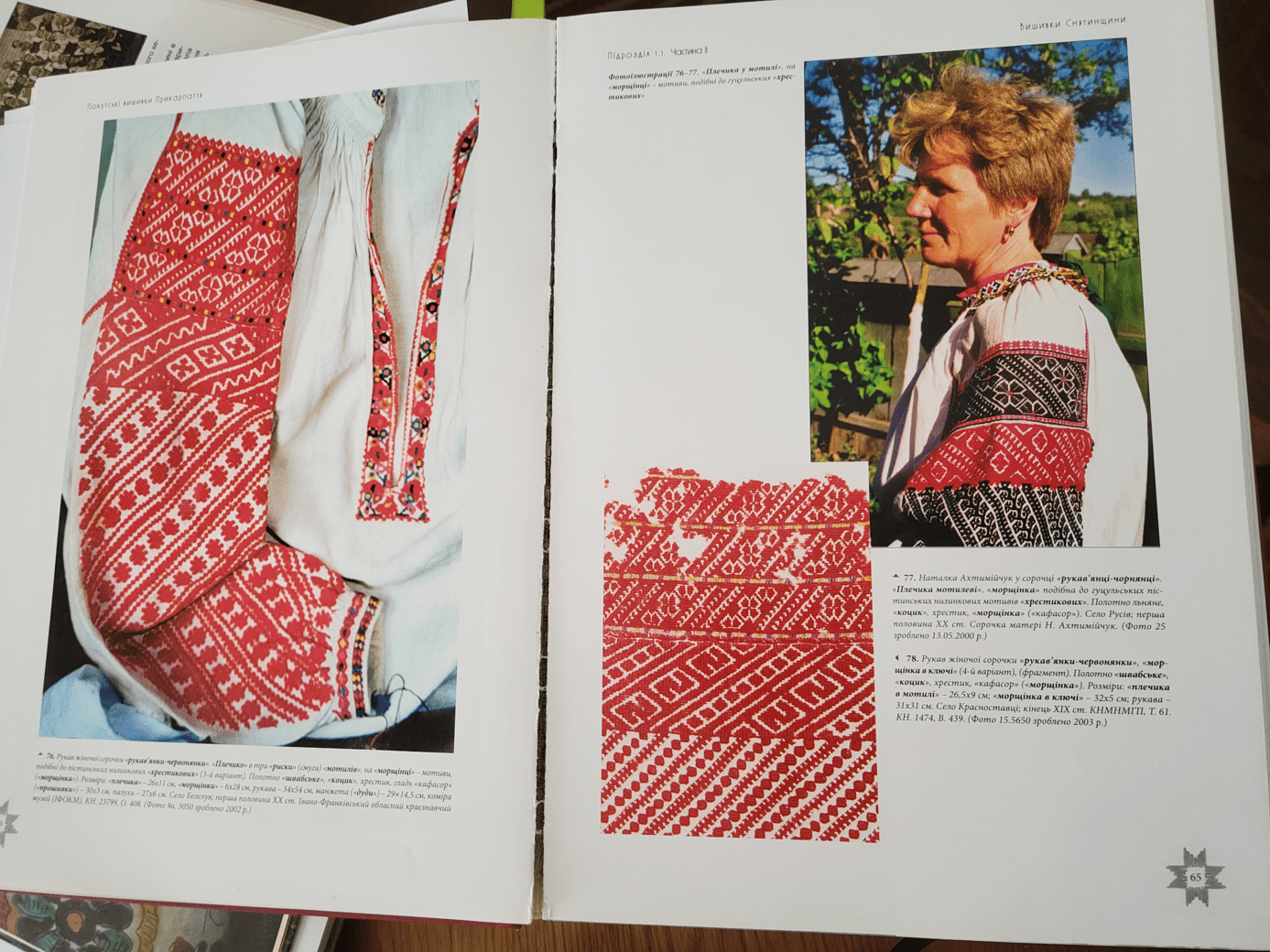

Sniatyn and its surrounding villages have a few different styles of embroidery for the shoulder insets. Here is a quick breakdown of the different types of embroidery patterns found in Sniatyn (listed here & in Iryna Sviontek’s work):

-

Red geometric embroidery, typically with some other color highlights (black, orange, green, blue, etc.).

-

Black geometric embroidery, with some other color highlights. This is uncommon in Sniatyn, but unsurprising because many regions in Western Ukraine predominantly embroider in black.

-

A combination of geometric red and black embroidery, often with some other color highlights. In this case, the pattern usually alternates (red, black, red…).

-

Geometric whitework with either red or color highlights (black, orange, green…).

-

Colorful floral patterns (purple, blue, orange, pink, green, etc.).

-

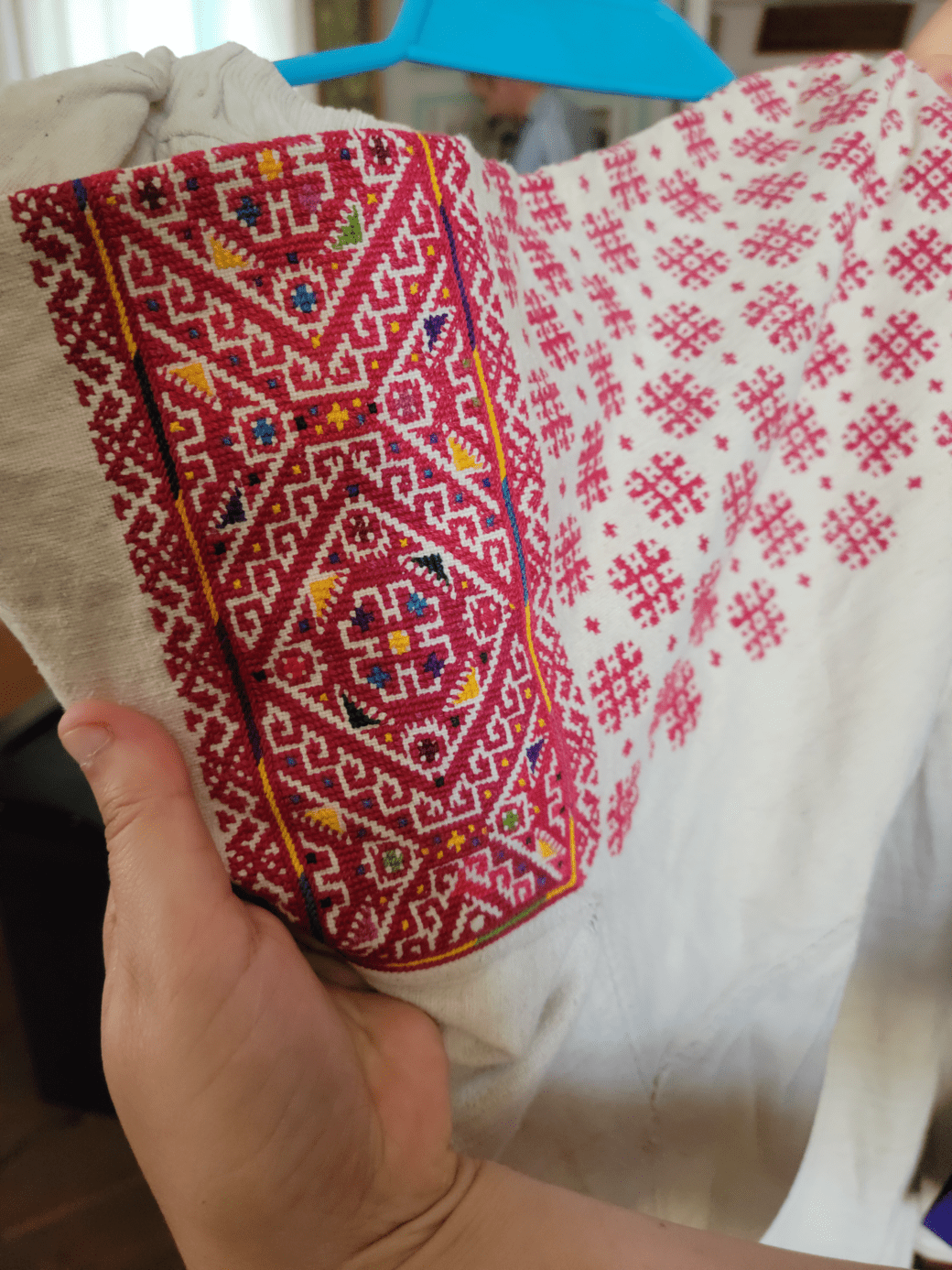

NB! Sometimes you may find a Sniatyn sorochka with more Hutsul-like embroidery (extremely colorful geometric patterns) in the Sniatyn region, such as this one from 1936. This is also unsurprising, as trade and festivals in the region allowed a good amount of contact among Sniatyn residents and the Hutsuls. So, this intercultural exchange should also be acknowledged.

While geometric patterns are the most ancient type of embroidery for the region, all of these types of embroidery have been in use in Sniatyn since at least the 19th century and are free for the Sniatyn embroiderer to choose from. Once a specific style was chosen for the inset, the patterns would be chosen to coordinate with this style. Colors may be changed in order to ensure that the style is followed.

Since I chose to embroider in the red & black geometric style, I will be focusing more on this style throughout this post. Red and black are, of course, two very traditional colors in Ukrainian embroidery. The color red has been tied to happiness and luck, whereas black generally symbolizes the black Ukrainian soil and wisdom. Other colors have also been historically used and tied to certain meanings, such as blue (protection, especially for men), yellow (sun and wheat), and green (Spring and youth). Of course, do be mindful that there may always be regional differences to these colors and meanings.

Geometric patterns would consist of a number of different designs, such as: diamonds, squares, pound signs, stars, crosses, triangles, etc. Some examples of these geometric designs may be found on this webpage and in my photos from the Sniatyn ethnographic exhibition. These geometric designs would usually be repeated throughout the entire sleeve.

Shoulder insets worked in the first three styles typically consist of a few different parts, though there are certainly exceptions. Most shoulder insets start at the top with (1) a small repeating pattern, such as stars. Under this small pattern would be (2) a larger pattern done in cross stitch. Below this pattern would be (3) another large pattern embroidered in flat stitch. Between these three patterns would be additional borders, such as solid blocks of varying colors or diamonds. Below this shoulder inset would be coordinating running patterns (such as vines or stars) down to the cuffs, if so desired for the shirt. On the other hand, whitework would generally have fewer patterns, and floral styles had much more freedom in construction and placement. These are just some generalizations, however, so please do note that there are sleeves that defy these constructions.

Cuff Patterns

In contrast to the shoulder inset, a lot of independence was given to the cuffs. It was not required for the cuffs to be coordinated with the rest of the sleeve. The cuff patterns may be composed of a variety of stitch types and colors, with not much regard to the patterns above them. For example, sleeves done in whitework may then have a cuff in redwork, and sleeves done in geometric redwork may then have very colorful, floral cuffs. Freedom is given to differentiate between the shoulder inset and cuffs.

Since there was a lot of freedom given to the cuffs, it is difficult to break down the different styles, like with the shoulder insets. Colorful embroidery patterns with floral, spiral, heart, etc. motifs appear throughout the various cuffs. Nyz’ embroidery may also be found on the cuffs. There are a few examples of these different cuffs on this webpage and in my photos from Sniatyn.

Designing a Sleeve

Once the embroiderer is familiar with the different Sniatyn styles, patterns, and stitches, they may then decide on how best to design their sleeves. This design process requires serious consideration since the embroidery is meant to reflect and serve the wearer and the context. Historically, this meant that embroiderers would pray and meditate on their designs to reach some clarity on how to design the sleeves. As mentioned above, the embroidery is meant to fulfill self-expression, aesthetic, protection, and context (wedding, etc.), which would all be factored into the embroiderer’s final decisions.

For example, if a woman is embroidering a shirt for her Greek Catholic wedding, she may pray over her design and reach some final decisions, such as: the shirt should be covered completely in embroidery from inset to cuff and multiple colors are desirable for the bride on this happy occasion. The final shirt would then be tailored for the bride and made with good intentions for a long and happy marriage.

Personalizing embroidery is a very important and treasured part of the design process. The embroiderer is not expected to follow a standard pattern, but instead reflects on the best way to imbue the embroidery with the personality of the wearer and best intentions for the context in which the embroidery would be worn. Ideally, no two folk embroidery patterns would be exactly the same, because each one is made for one person and their life. To guarantee this ritual of self-expression and personalization, embroiderers are at liberty to choose the patterns for their sleeves and to change their foundational patterns. For example, two shirts may share one pattern on their shoulder insets, but one shirt uses black for the pattern, whereas the second shirt uses red. Patterns are altered in order to make them unique for the shirt. This also ensures that the chosen style may be followed; for example, changing one pattern from red to black may then allow the embroiderer to make a red & black-styled sleeve.

I press the reader to remember that Ukrainian folk embroidery is meant to be personalized and altered to fit the wearer’s personality and their context – it’s an extremely important part of the embroiderer’s ritual of self-expression and, therefore, intangible cultural heritage. By honoring and following this ritual, we honor our embroidering ancestors and the traditions tied to the craft; my great-grandmother had her aesthetic and I have mine, but we both meet at the crossroads of embroidering. Moreover, this personalization lets us contribute to Ukrainian culture, diversify it, enhance it, and carry it into the modern day with us. Innovations and self-expression in the craft are just as welcome among Petrykivka painters and sopilka crafters. Culture is always and constantly changing, and to see changes in craft by crafters is a hopeful sign for the future of Ukrainian folk culture. Self-expression in craft is at the core of Ukrainian culture; without it, we would lose an invaluable part of our history and culture.

Designing my Sleeves

My sleeves are very personalized while still following the typical guidelines of Sniatyn embroidery. Since I was crafting my vyshyvanka for this MA project and for casual use, I decided early on to focus on my shoulder insets and cuffs. This ensured that I could finish crafting the most vital elements of the embroidery within my limited time. So, for this vyshyvanka, the running embroidery between the insets and cuffs has ultimately been omitted. I’m hoping that I can begin including this third part in future shirts when I am not held to such a tight timeframe.

When approaching my sleeve design, I focused on incorporating the ritual of self-expression and elements of protection. I chose the red & black style early on to showcase the diversity of patterns and colors in Sniatyn embroidery. Personally, I also like how the red and black complement each other in this style. I find it aesthetically pleasing and actually rather distinctive of Sniatyn embroidery; other neighboring regions, like Bukovyna, do not typically switch between blocks of color as jarringly as Sniatyn embroidery does, making it rather a unique design. Along with the choice of colors, this inherently meant that I would be embroidering Sniatyn’s older geometric designs. I suspect that Olena Pchilka would be thrilled to find that the ancient geometric patterns of Sniatyn embroidery are still being crafted today! In any case, this emphasis on red & black geometric patterns helped me start narrowing down my patterns.

Shoulder Insets

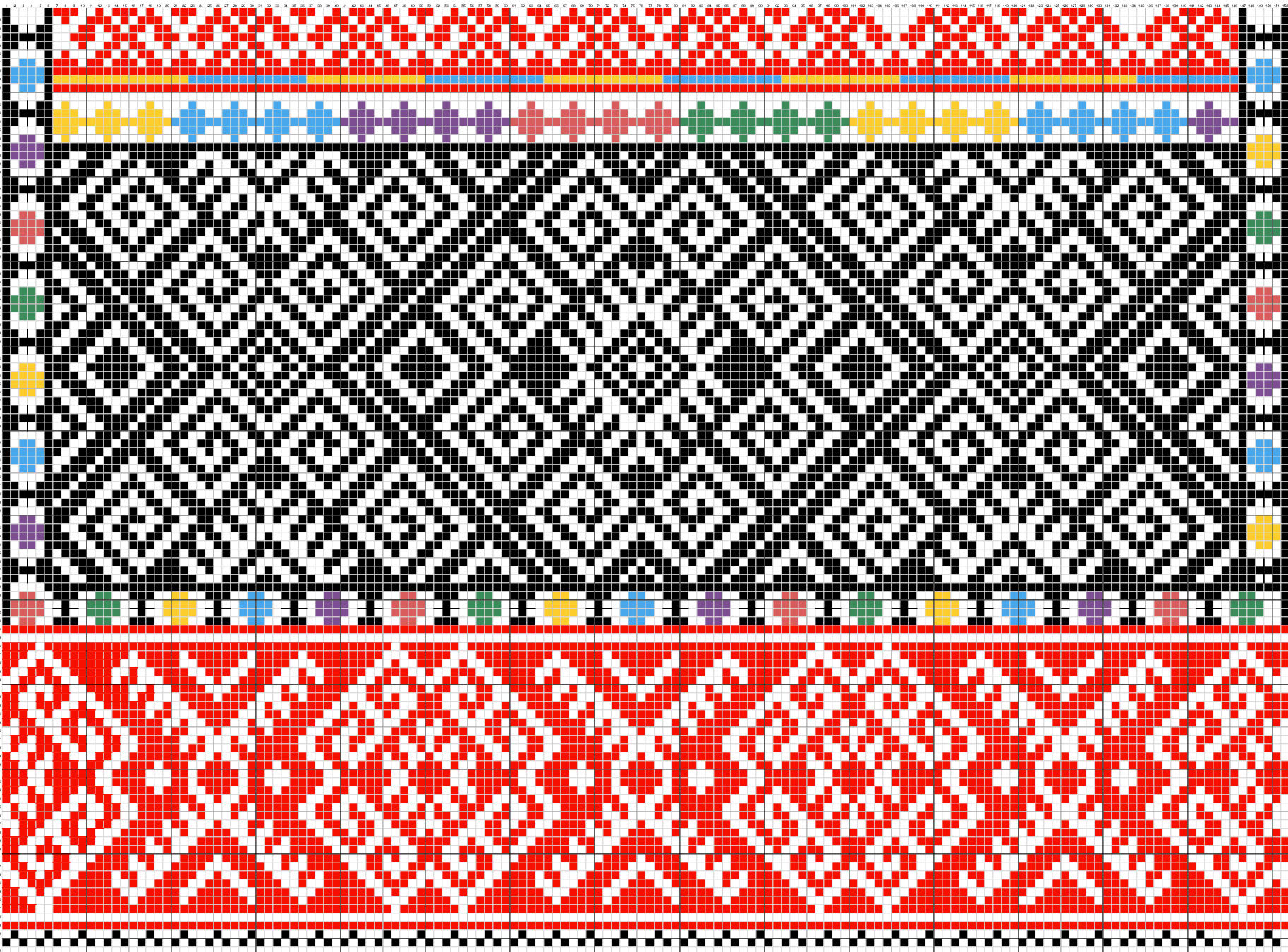

The design for my shoulder insets went through two different drafts, as I tried to figure out which elements and designs worked together best. I drafted both possible designs using Stitch Fiddle, so that I could be absolutely sure of my decision before beginning the embroidery process. I will cover my first attempt and why I didn’t choose it in the end, then explain the various design elements in my final sleeve design.

The first design was composed of a couple of patterns that were also incorporated into my final sleeves, namely the top Berehynia figures and the red nyz’ pattern. Its center focus was, however, a heavy black pattern bordered with diamonds in various colors. I did not change any of the colors or details in these patterns from their historical precedents, but instead took them straight from the originals and rearranged them for my own design. Now, color-wise, I would like this construction for a sleeve that is mostly covered with blackwork, as it would make the red nyz’ pattern extremely distinct against the otherwise mostly black sleeve. However, the doubling up of heavy blocks of color made this a really heavy design that, in the end, felt unnecessary and even stifling for this particular vyshyvanka. For my vyshyvanka, in this current context, I wanted a lighter design that would showcase the beauty and happiness of Sniatyn embroidery. Although I still love the heavy black pattern, I decided to set it aside for my final pattern and replace it with a different design that would be a bit brighter and less complex. I might revisit this design again someday to see if I can improve it, but for now, I have settled on my second altered design.

For my second design, I decided to keep a lot of the elements from my original design but replace the 2nd pattern and bordering diamonds. I looked back through my photos from Sniatyn and landed on a beautiful pattern that had originally been redwork. This design had a lighter feeling to it and was even colorful – I felt rather compelled to include it on my sleeve. When redesigning my sleeve, I switched the new redwork pattern to blackwork, so that I could still follow the red & black embroidery style. As the new pattern uses various other colors to fill in the details, I also used different shades that would complement the black and my own preferences better. Most of these shades were chosen based on how they would look next to the black, though there were some exceptions: the blue and yellow shades were chosen to correspond with the Ukrainian flag, and I decided to replace the royal purple with a lavender purple, since lavender is a symbol of queer resistance (my Queer page is relevant here). When I put these elements together, I had a design that I was perfectly happy with: it followed the red & black color scheme, and it emphasized the treasured elements and diversity of Sniatyn embroidery. After a lot of reflection (and my usual bout of indecisiveness), I knew that this was the best design to represent myself (the wearer) and my final intentions for the vyshyvanka, including showing off the beauty and diversity of Sniatyn folk embroidery.

This final design has several elements that may be explained here:

1. Berehynia: This is the repeating pattern of red figures at the top of my pattern. It is worked in cross stitch. This pattern has appeared in a few different shirts from Sniatyn since the 19th century, typically in redwork. It is also used in pysanky designs. The Berehynia symbol depicts a female figure with her arms upraised. The common understanding today is that Berehynia is the protector goddess of the home and, more broadly, of Ukraine. This depiction of Berehynia as the protector goddess of Ukraine has been readily adopted over the past several decades. An artistic interpretation of her even crowns the Independence Monument in Kyiv, and she had been accepted as a national symbol of Ukraine. While I am always careful when applying meaning retroactively to past culture, it is clear that Berehynia occupies a very important place in modern Ukraine’s culture, at the very least. So, I have incorporated Berehynia into my own design as a symbol of protection and of my Ukrainian heritage.

The astute reader may have noticed that I made the cross stitches for my Berehynia larger than regular cross stitches. I chose to do this to give the pattern a bit more focus and to give it a bit of an “older” feeling to it that was more akin to the “messy” embroidery of 19th century shirts. I’m happy that I did this, as it does give my sleeve a bit more character beyond my otherwise “clean” stitches.

2. Diamond / Rhombus pattern: Following the style of other red & black embroidery, the pattern underneath the Berehynia is wide. This is also worked in cross stitch. This pattern is made up of diamonds (or rhombus) with the pound sign in the center and other elements (i.e., triangles, etc.) to decorate the diamonds. These basic geometrical shapes repeat throughout the pattern, adding cohesiveness to its overall design. There are some theories about what the individual elements mean, such as the diamond representing the earth and sun or fertility or plowed fields; you can find a brief overview here. Some of it may well be reconstructionism, so again, I am wary about automatically assigning meaning retroactively to these geometric patterns, and I am content to recognize the inherent significance of embroidery on its own. In any case, as mentioned above, I did switch this pattern from its original red to black so as to complete the red & black embroidery style, and the decorative colors are chosen to either complement the black base or for symbolic reasons (namely, to achieve the Ukrainian flag and to add a queer symbol to my work). I did follow the lead of the original pattern in terms of color placement; the same color mirrors itself in certain parts of the pattern, while the colors are randomized at other times. When designing the mirroring parts, I followed some form of color theory. With the randomized parts, I would use whichever color would bring the most cohesion to that part of the pattern. I had to switch colors around often, though, so eventually it just came down to the vibes I wanted for the pattern. Do with that what you will.

3. Red nyz’ pattern: Now switching back to red, the third pattern is another repeating geometric design. Like many other shirts, the third pattern in my sleeve inset is worked in horizontal counted satin stitches (for the Sniatyn region: cross needle over 4 threads in the fabric, go back 1 thread to draw the needle up, repeat). Like the second pattern, this one also incorporates a series of geometric elements, such as diamonds and arrows, to create a repetitive pattern.

4. Borders: And finally, like with other shirts, my embroidery has the individual patterns blocked with smaller patterns worked in cross stitch and diagonal flat stitches. In this case, I chose to use blocks of color to border each pattern. The Berehynia is bordered on the bottom with red cross stitches. The diamond pattern is edged completely by black cross stitches and diagonal flat stitches in various colors. And the nyz’ pattern is framed at the bottom by red cross stitches, with alternating black cross stitches underneath. Each border is designed to complement its corresponding pattern and to finalize my shoulder inset.

And with that, I had a centerpiece to my folk dress that I was happy with! Now that I have embroidered the pattern, I can say that I think I did a good job with this design. My shoulder inset could easily fit in with the designs of the older shirts, and it suits my personality and context very well. For this being my first shoulder inset, I’m really proud and happy with it. This definitely has given me the confidence to keep working with geometric Sniatyn patterns in the future.

Cuffs

I was actually well on my way into embroidering my shoulder insets when I got around to the cuff design. Partially because I wanted to wait until I really knew what the embroidery would look like, but also partially because I wanted to wing it. The cuffs are often independent from the shoulder inset in terms of coordination, so I have come to think of them more as a separate entity.

When it was time to think about the cuff design, I started looking through the different photos… and I didn’t like a lot of them. A lot of the cuffs are pretty jarring in terms of suddenly switching to bright colors or floral patterns. I didn’t need my cuffs to coordinate entirely with my shoulder inset, but I still wanted some sense of cohesion for the whole shirt. Another recurring problem was that, even if I did find a pattern that fit my preference and existing shirt, I couldn’t pull the exact pattern due to grainy photo quality. I found one cuff on a red sleeve, for example, that I really love, but the photo quality makes it difficult for me to figure out the pattern. But I did eventually find a cuff pattern that I liked for my vyshyvanka and that I could figure out easily.

It’s also a very popular pattern for Sniatyn-based cuffs. It’s everywhere.

This particular cuff pattern is geometric, featuring diamonds and other geometric elements that match my shoulder inset. This cuff is worked in nyz’, meaning that it is embroidered with a counted satin stitch that forms a pattern on both sides of the fabric. This design includes heavy embroidery right below the geometric pattern, likely to reinforce the edges of the cuffs. Although I have seen it appear across multiple shirts, I haven’t seen it appear exactly the same on two different shirts. Here are a few examples:

-

The cuff I based mine off of is in the Sniatyn ethnographic collection. It is a maroon color, has accents in multiple colors, and has an exaggerated cross in the middle of the diamond. This one is paired with a red sleeve.

-

This cuff is also maroon, but it is missing the cross in the middle of the diamond as well as the color accents. This one is paired with a sleeve of whitework.

-

This cuff is maroon, has multicolor accents, and has a cross in the middle of the diamond. Unlike the cuff in the ethnographic collection, this cuff has more open spacing and is heavily bordered with black. This cuff is also paired with a red sleeve.

-

Unfortunately, the photo is a bit grainy, but this cuff appears to be completely black. The color accents are missing here as well, but the cross is present in the middle of the diamond. It is paired with a red sleeve.

When approaching my design for this cuff, I decided to follow the model of the one that I had seen in the ethnographic collection. I had been able to take a close-up photo of this cuff, so I was able to replicate the pattern as exactly as possible. So, my spacing for my cuff is close to the original cuff. I also decided to keep the maroon color for both the geometrical pattern and the border underneath the pattern. Color accents are also present in my pattern, though I did use the same colors as my shoulder inset, so the shades are different from the original, naturally. The one notable change I did make was to replace the cross in the middle of the diamond with another, smaller diamond. Considering that another of the cuffs linked above has also removed the cross, it would appear that I have not been the first to change the exact pattern at this part. The result is a cuff design that is quite close to the one in the ethnographic collection, but which has been personalized to set it apart from the others, as the other embroiderers have done with their cuffs.

I’m really happy that I chose this pattern. I’ve had very limited opportunities to work with nyz’ before, so I appreciated the chance to incorporate this old stitch into my own vyshyvanka. I like that this cuff pattern is so popular among Sniatyn embroiderers; I love it, personally, and it’s been really cool to identify all the different variations in this pattern over the past several months. It also complements my own vyshyvanka and style very well, so it was certainly a good choice.

And with that, my embroidery design is completely finished! Readers looking to see the embroidering process and photos of my own work may now head over to the Vyshyvanka page for further details.