Fieldwork

In order to make my folk dress, it felt rather important to first visit Ukraine. So, in early to mid-July 2023, I stayed in Western Ukraine (mostly the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast) to do fieldwork.

From a purely project-based perspective, this fieldwork makes sense. I’m covering my family’s hometown of Sniatyn, which is small and not extensively written about online. Accessing patterns and other information about Sniatyn textiles abroad was increasingly challenging, and I had a difficult time verifying the legitimacy of the few sources that were readily available. While preparing for my MA degree, it felt more and more vital that I visit Ukraine for myself and go to see the textiles for myself. By January 2023, I was already actively planning my fieldwork visit in the summer and looking for museums to contact. In the months leading up to my departure, I watched the news and read up on what I needed to know before going to Ukraine.

But these logistics aside, it was also time for me to visit Ukraine. No one in my family has returned to Ukraine since the initial deportation during WW2. The closest any of us have gotten was my older cousin, who, in her younger days, had taken a guided, English-language tour of Poland. But going to Ukraine hadn’t occurred to any of my relatives as a reasonable possibility until I came along. By the time I started this MA program in Estonia, I was already the best-prepared member of the family to go to Ukraine – I’m younger, don’t have health complications, had the financial means between my mom’s help and my savings, had the interest to go, and had at least basic Ukrainian speaking skills. I’ve spent the last several years of my life rebuilding our family’s true narrative and learning about our original Ukrainian heritage. It was the first time since WW2 that someone in my family was well-informed and well-positioned enough to pay a visit to our ancestors’ hometown, and even this feels long overdue.

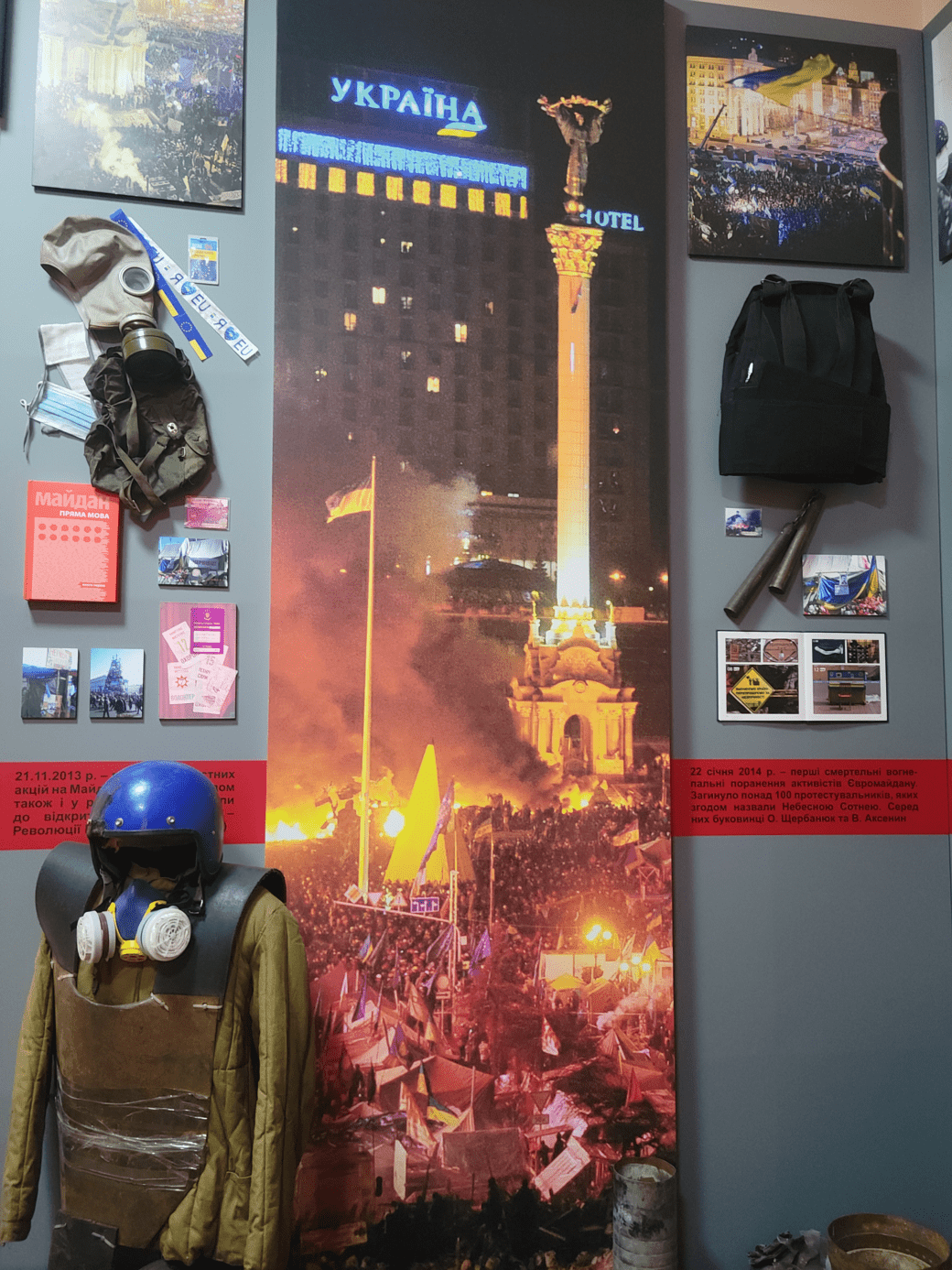

I am not oblivious to the war. I’ve been following it since the days of Euromaidan in 2014. But the Russians have already stopped my family from returning home once, and at my first chance, I wasn’t going to let them stop us again. I visited with the support of my mom and my aforementioned cousin, and with emphasized thanks to the Ukrainian armed forces, I traveled to and from Ukraine safely. And this fieldwork trip was completely worth it – not just for my folk dress, but for the strengthening of our ties back to Ukraine. My time there was truly unforgettable, and I am already looking forward to returning someday for good reason.

Lviv

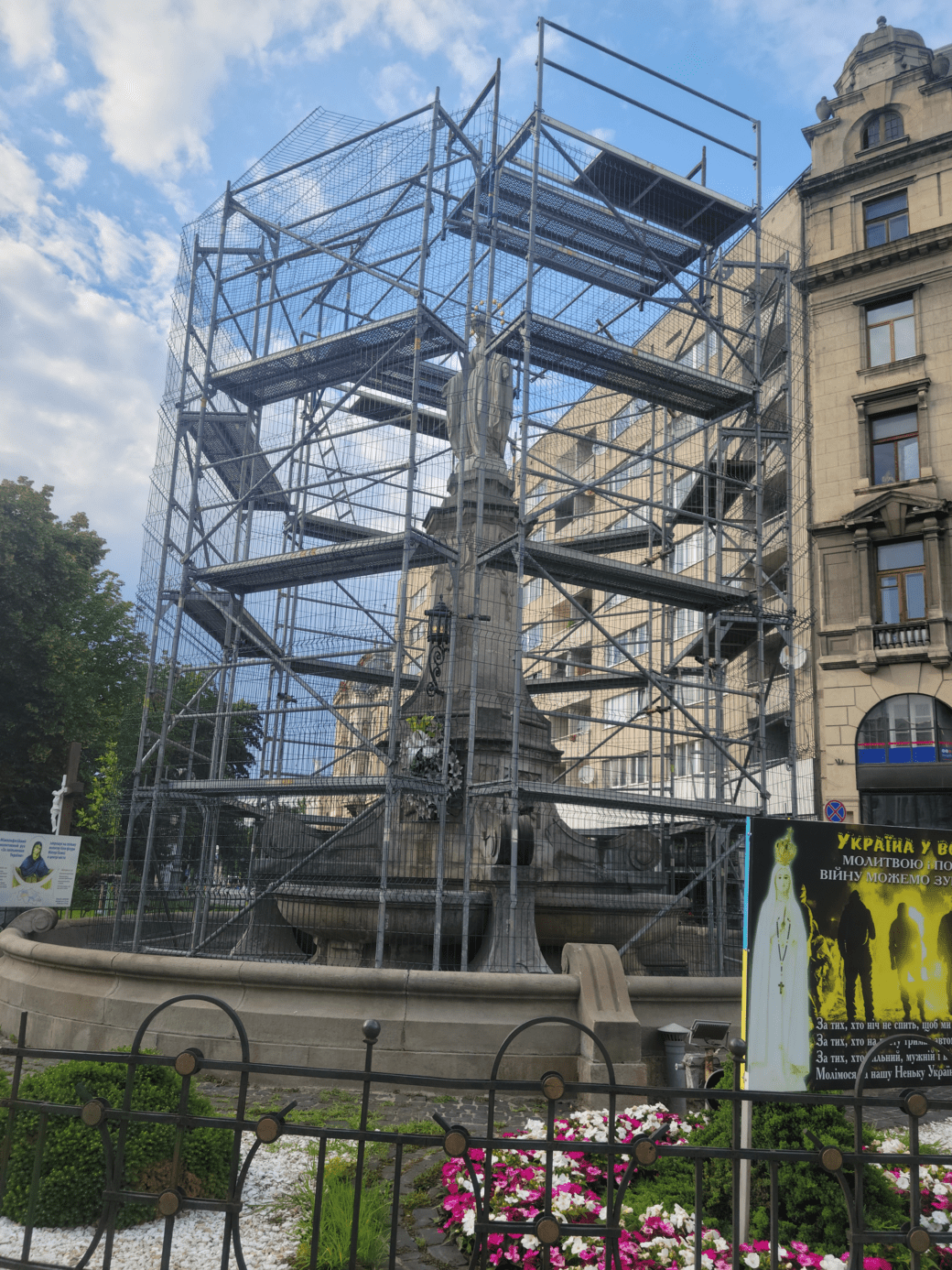

Lviv was the first city I stopped in, following 26 hours of travel from Tallinn. Getting through the border was surprisingly quick when I entered Ukraine, in contrast to when I was leaving and got stuck at the border for roughly 10 hours. In any case, I decided to take a 24-hour break in Lviv before moving on to the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast. I am, admittedly, not a big fan of large cities, and Lviv was very busy, so I didn’t care to stay long. I also don’t have many photos from Lviv to show here, as I try to avoid taking photos of strangers, even when doing touristy things. The cloudy weather during my stay there also didn’t help much for photo-taking. I will offer a photo of a fine Lviv pigeon instead, as well as one example of how Lviv residents have prepared their monuments for the war.

Since I was on limited time there and was looking at several museum visits ahead of me, I opted not to visit any museums in Lviv. Instead, I spent my day there visiting various shops to collect embroidery books and see for myself how popular folk textiles are even today. The number of shops selling vyshyvanky, etc. just around the town square was honestly impressive. Nearly every tourist shop sold vyshyvanky, either according to the historical cut or replicated with t-shirts. As I mention on the Silyanka page, Lviv is even where I truly discovered the silyanka necklace and began my own collection.

But it wasn’t just the tourist shops that were covered in vyshyvanky. Everywhere I looked around Lviv, I could find women wearing (usually machine-embroidered and modernized) vyshyvanky, silyanky, or some other echo of historical folk dress. In the diaspora, I had seen women wear their vyshyvanky on special occasions like Vyshyvanka Day and Ukrainian Independence Day, of course. But in the streets of Lviv, I saw every type of vyshyvanka in every color and style imaginable on otherwise ordinary days. To see the vyshyvanka integrated into modern fashion is, for me, really amazing. Though, to be clear, a lot of the renewed enthusiasm for the vyshyvanka/etc. is most likely in response to the war. I’ve talked to a couple of Ukrainians before who, after witnessing the protests of Euromaidan, began purchasing modernized vyshyvanky and wearing them regularly. Still, to see how popular vyshyvanka/etc. were in the streets of Lviv was inspiring for me as an embroiderer!

The other benefit to Lviv was, of course, that it had good coffee (something that I sorely miss in Estonia).

Kolomyia

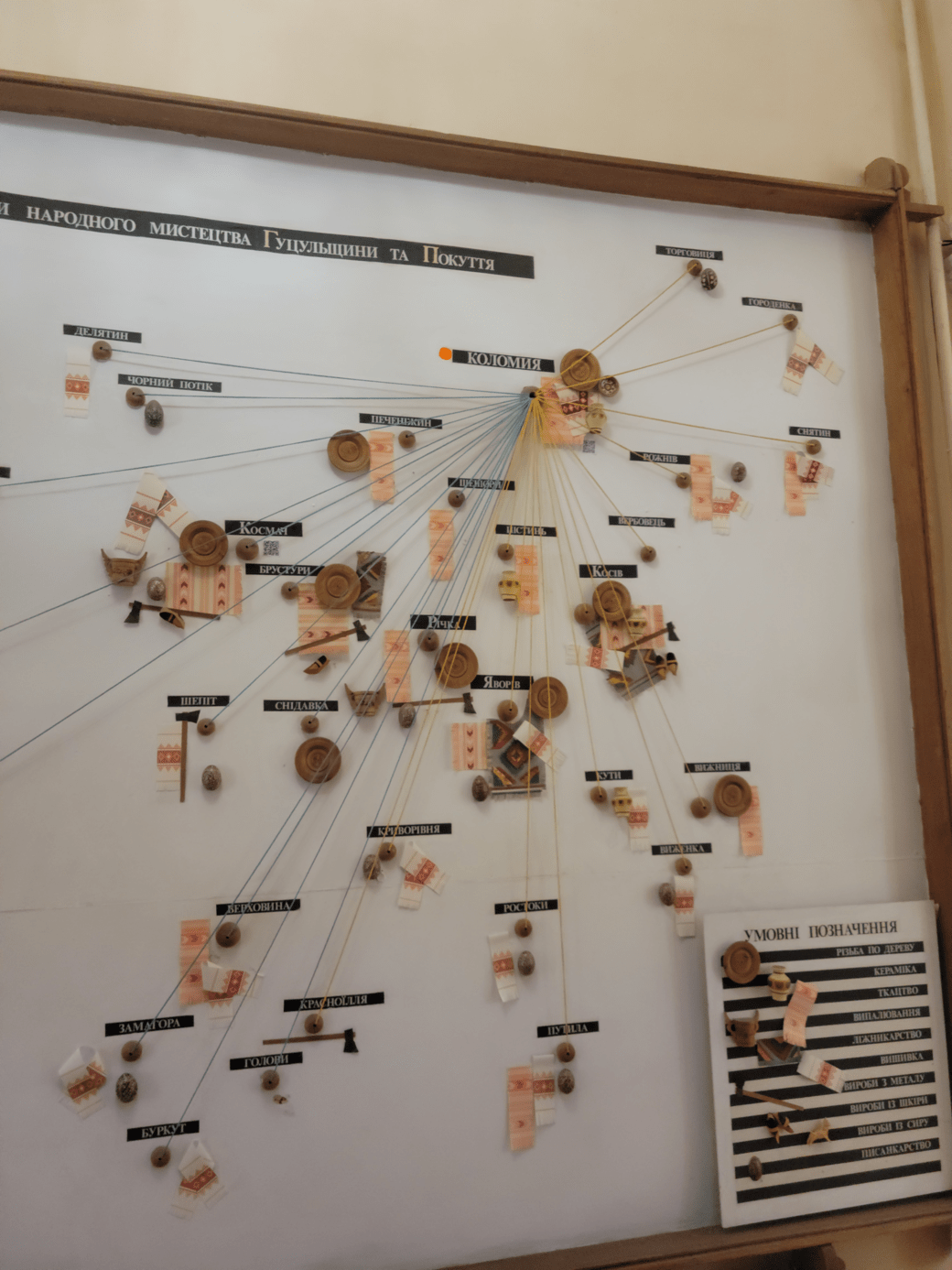

The remainder of my time in Ukraine was spent in the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast. Kolomyia is one of the larger centers in the area and is the place to go for information on the Pokuttia region. In the months before my trip, I contacted the staff at the National Museum of Hutsulshchyna and Pokuttya Folk Arts to book a tour of the museum in English and to ask them for further contacts who I could speak to about Pokuttian textiles. The National Museum has connections to several different institutions and folk crafters around the region, so they were the best place to go to for building a network. This especially became evident when I saw a board where the museum was keeping tallies of which crafts were still maintained in which towns (including Sniatyn!) across the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast. Luckily for me, the staff was very helpful and aided me in accomplishing my fieldwork, for which I’m eternally grateful.

The National Museum also, obviously, has an extremely extensive collection of… well, everything! Woodwork, musical instruments, belts, axes, pottery from Kosiv, looms, skirts, embroidery, silyanky, knitwear, rugs, crowns and hats, an entire replica of a 19th-century wooden peasant house… They even have a resident cat! I walked away from that museum with 330+ photos, many of them of their textile collections. I have used a few photos from the museum throughout this blog, but the amount of data I still have left from that single visit is incredible (in other words, my tech guy would probably yell at me if I tried to include all of them here). I can’t recommend a trip to Kolomyia enough for anyone interested in Ukrainian folk culture.

While there, I also visited the Pysanka Museum to see the last remnants of the local textiles collection. There’s also a certain thrill in being able to say that I went inside a giant pysanka in order to see many little pysanky. There were thousands in there; it was, frankly, a little overwhelming for someone who is really bad at writing pysanky. But I did find one really interesting exhibit in the Pysanka Museum: a diaspora exhibit! They had a permanent collection of different pysanky written by Ukrainians across the world. I would get more reminders about this in Sniatyn, but this was the first time in Ukraine that I had seen how Ukrainians still remember and care for their diaspora.

Beyond these museum visits, Kolomyia was also my main place of stay while in Ukraine. While it’s still a pretty central location for the oblast, Kolomyia is still a small town in a small oblast. This setting was more comfortable for me personally, but it also meant that I was relatively safe. I knew where the local shelters were and had the air raid alert notifications on my phone (which did go off a couple of times during my visit), but this was probably the closest I could get to safety in the context of the war. Fieldwork-wise, it was also an advantageous choice; Kolomyia is a central location for the Pokuttia region, and I was able to take public transport to the rest of the towns that I visited.

Otherwise, I enjoyed my time staying in Kolomyia. Their local embroidery supplies store was well-stocked; I even found my favorite koraly necklace there (see my Accessories page for further information). It was a pleasant town to walk through, had a few really cute cafes to sit at, and was lively – what more could I ask for?

Ivano-Frankivsk

Ivano-Frankivsk was the first city that I took a day trip to outside of Kolomyia, and I visited two more times after that. Like with Lviv, I don’t have a lot of photos from Ivano-Frankivsk to share. I started taking touristy photos, but then quickly ran into a sign instructing to not take photos anywhere near their governmental buildings (which makes sense right now), so I stopped taking photos as much after that. I also didn’t want to take photos near the Alley of Glory to Fallen Heroes, which spans the area of Ivano-Frankivsk that I frequented the most. There were a few times that I saw mourners visiting the posters of their fallen loved ones to bring fresh flowers and candles, and I just can’t fathom invading their privacy for the sake of tourist photos. So, if there’s any disappointment in the lack of tourist photos on this page, please note that my visit was still very much within the context of the current war, and I wanted to respect that.

To be honest, my first visit was for the purpose of getting a tattoo. Ukraine has some amazingly talented tattoo artists, so I stopped to get a tattoo of flowers and kalyna berries. That took up most of my first day in Ivano-Frankivsk. My next visits were focused more on finding accessories that I needed for my folk dress, but was having a difficult time finding in Kolomyia. The one photo I can offer here is of the store from which I bought my crown. I include more details about this on the Accessories page, but Ivano-Frankivsk is where I got my first belt, a couple of necklaces, and crown. These were things that I knew would benefit my folk dress but would be difficult to find once I left Ukraine.

The one family-related goal that I did set and accomplish for Ivano-Frankivsk was to see where my great-grandparents and grandmother lived on the eve of WW2. I have an old census record for their household from August 1939, when Ivano-Frankivsk was called Stanisławów and was a part of independent Poland. This census record noted their home address, and after looking through a list of street name changes in Ivano-Frankivsk, I was able to locate the exact street where they used to live. It wasn’t far from the train and bus stations, so visiting the neighborhood was easy enough. Their exact address no longer exists, but it’s a small neighborhood, so it’s likely that I saw roughly where they once lived. My great-grandfather had worked for the nearby railway before the war, so it was interesting to see the exact shortcut and path that he used to take between work and home. There’s so little that I can trace of his lifetime, but for one afternoon, I followed the same paths that he used to walk ~90 years ago.

Chernivtsi

After visiting Ivano-Frankivsk the first time, I took a day trip over to Chernivtsi. Chernivtsi is the administrative center of the Chernivtsi oblast as well as the former capital of the historic Bukovynian region. As such, Chernivtsi is the best place to see textile collections from Bukovyna. Spending some time looking through the Bukovynian textile collection in Chernivtsi was an important task for me since Sniatyn sits on the border of Pokuttia and Bukovyna – really, Sniatyn is only 35 km from Chernivtsi. As such, Sniatyn textiles are undeniably influenced by the close proximity to Bukovyna. So, I took a train over to Chernivtsi to see the similarities and differences between Sniatyn and Bukovyna textiles for myself.

The main Bukovynian textile collection is held at Chernivtsi’s Museum of Regional Ethnography. For this museum visit, I didn’t book a tour, but luckily each exhibit was well-labeled. Like the National Museum in Koloymia, the Chernivtsi museum is delightfully extensive. They had exhibits on the local flora and fauna, city life at the turn of the century, technology throughout the past century, and even Euromaidan. Their rooms also held a lot of folk arts, including folk dresses, jewelry, musical instruments, pysanky, and tools of various sorts (such as for processing linen and spinning yarn).

The museum’s textile collection really is quite massive and features several different styles of Bukovynian folk dress. Bukovynian textiles incredibly diverse and incorporate so many different styles; to be honest, purely based on aesthetics, their folk textiles are my favorite from Ukraine. Bukovynian embroidery and woven fabrics are so creative and limitless within their historical form, and they always seemed to be on the forefront of progress when developing their dress. While I can certainly see the similarities between Sniatyn and Bukovynian dress (such as the straight silhouette, richly embroidered sleeves, and pattern types), Bukovynian dress is truly on a level of its own that I can only aspire to with my own textile craft. But I’ll try not to gush too much about their folk dress throughout this blog. Moving on!

Chernivtsi itself was a nice city to visit for the day. Its center is filled with beautiful architecture and cute streets to walk through. I am hoping to return to Chernivtsi again someday so that I can visit its Regional Museum of Folk Architecture and Art, which looks quite interesting.

Sniatyn

Of course, the crowning jewel of my fieldwork trip to Ukraine was my visit to Sniatyn.

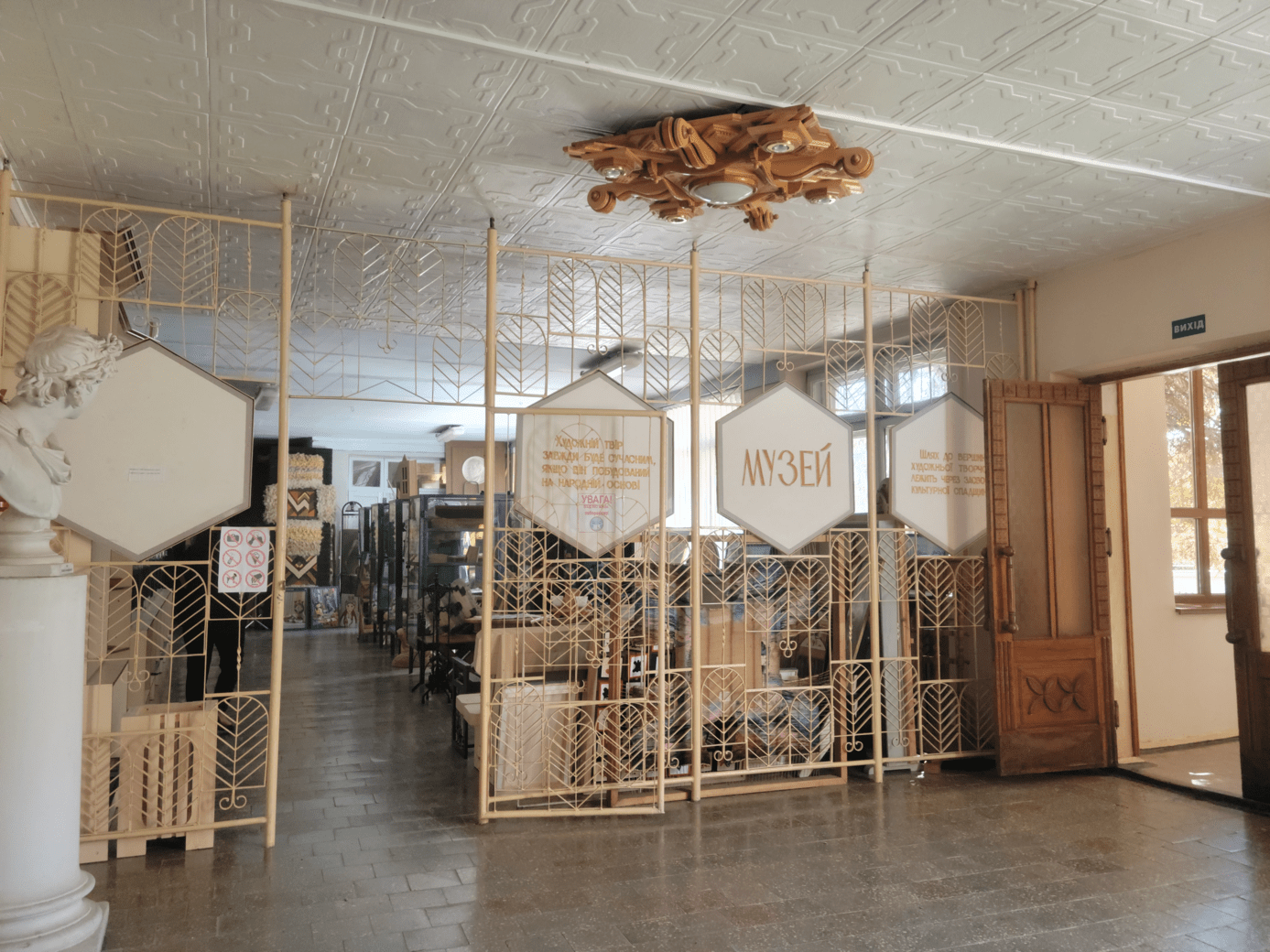

The staff at the National Museum in Kolomyia helped get me in touch with Ivanna Stef’yuk, the curator of the ethnographic exhibit at Sniatyn’s Marko Cheremshyna Literature and Memory Museum, where the only public collection of Sniatyn folk textiles is kept. I was able to book an English-language tour of their exhibit in advance, and arranged to visit Sniatyn first thing in the morning. The exhibition itself is quite small and has a limited number of textiles (as shown in the 3 photos of the museum here), but I was able to see everything up close and take detailed photos of every single folk dress in their possession. Ivanna kindly introduced each item to me, answered my questions about Sniatyn embroidery, and even let me record an excerpt of her speaking in the Sniatyn dialect. She also showed me several books in their collection, including a couple that had been written by members of the Ukrainian diaspora – another confirmation that Ukraine still remembered her diaspora. Upon my parting, she also gave me a brochure for Sniatyn and a copy about Marko Cheremshyna, which was a very nice surprise. This trip to the museum was very successful, as demonstrated in section 3, where I use the information that I collected in the Sniatyn museum to craft my own folk dress. I’m so grateful to Ivanna for agreeing to give me a tour of the ethnographic exhibit and thereby enable me to craft my own Sniatyn folk dress.

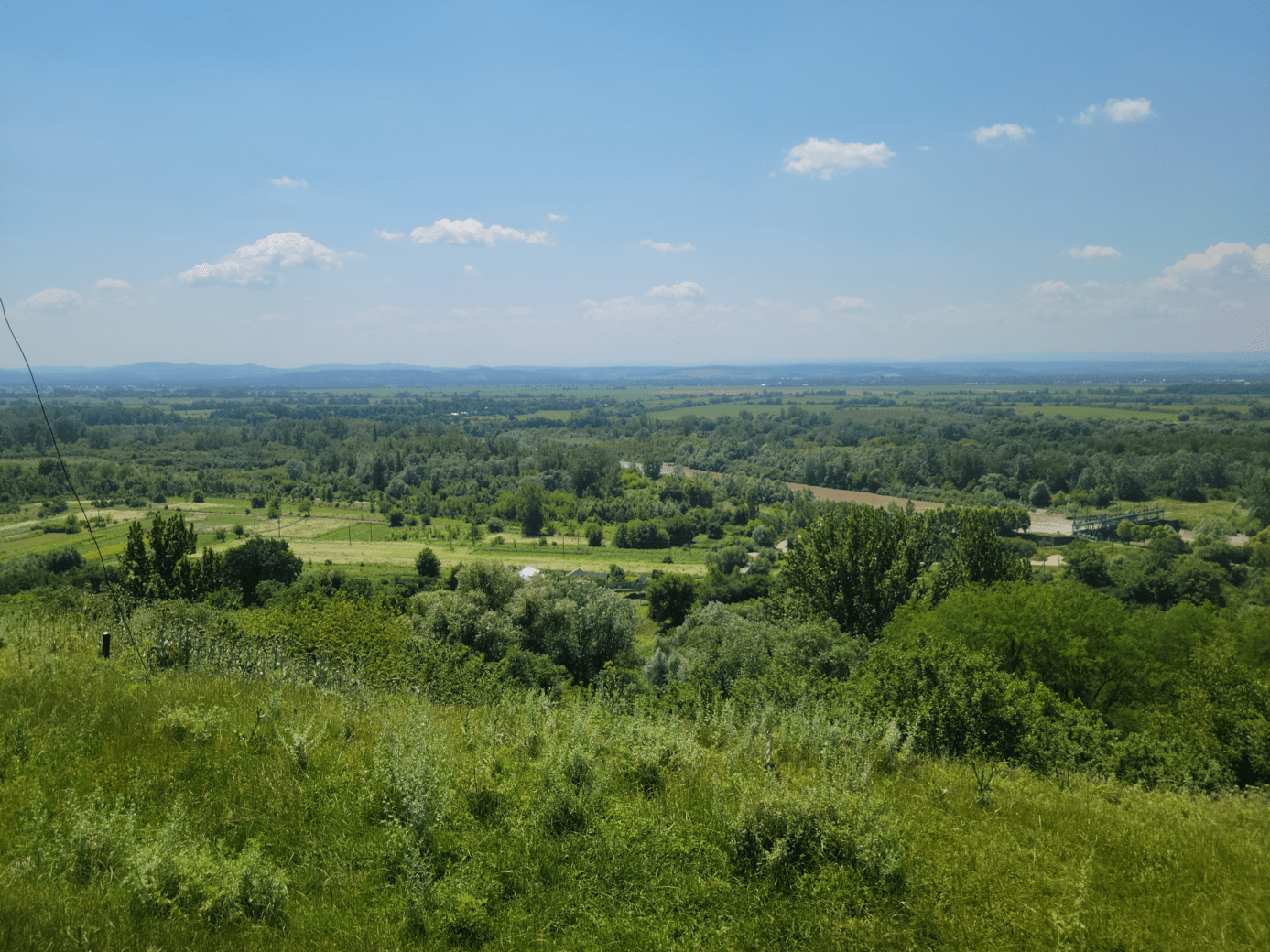

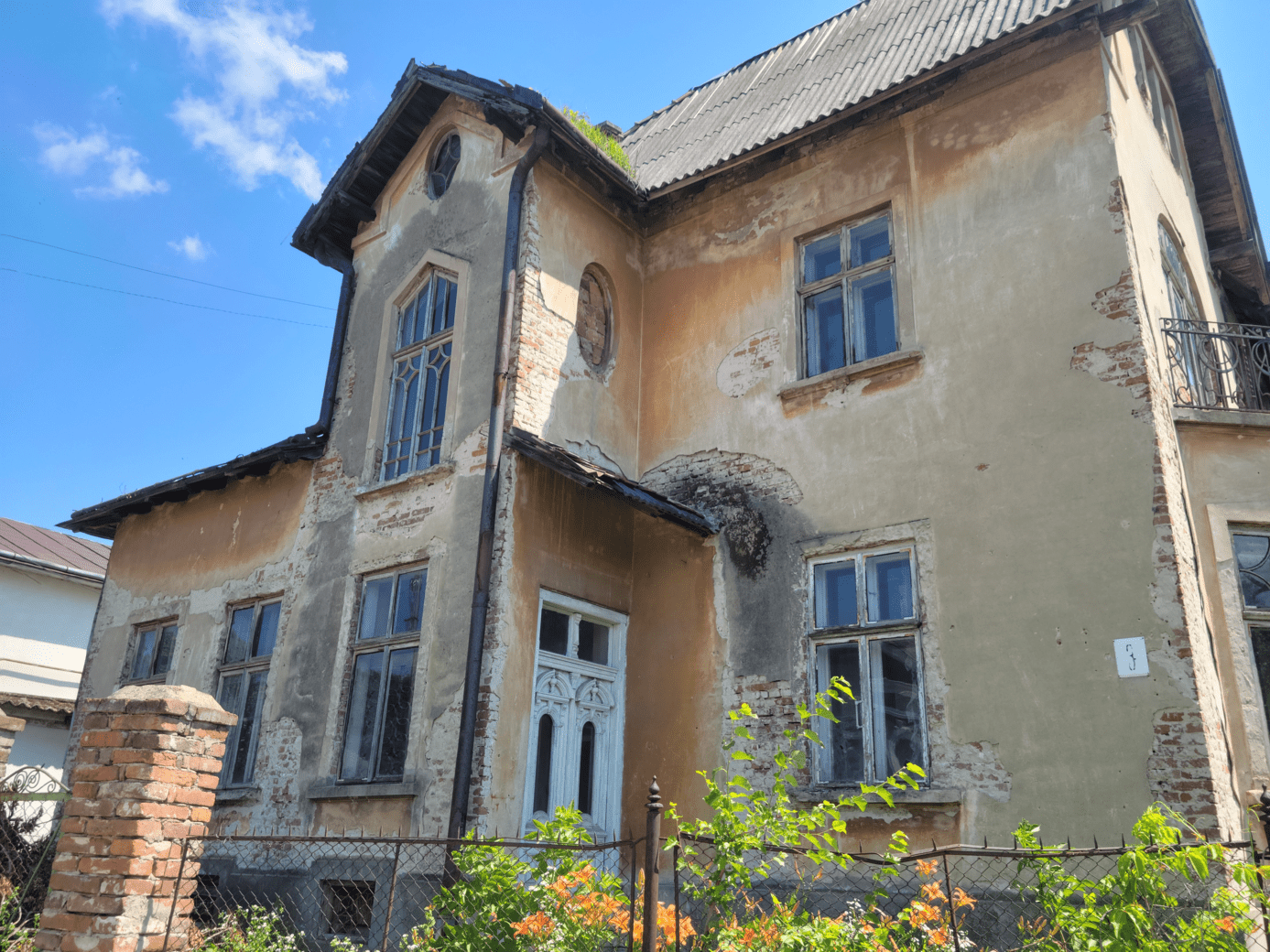

This wasn’t the end of the museum staff helping me, however. Although this was my family’s hometown, I kept my hopes in check when visiting Sniatyn and opted to just focus on the textiles and town itself. Just being the first in my family to go back was already a huge deal for my mom and older relatives. But while I was venturing through Sniatyn on my own, I ran into Petya Kireev, the head of the museum. We had met briefly while I was touring the exhibit – he seemed excited about my visit, since he could practice his English and liked my tattoos – and learned my name from Ivanna. He stopped me in the center of Sniatyn and offered me a tour of the little downtown area, which I accepted. He showed me the historic buildings (including a haunted house!), local Greek Catholic Church (which was built between 1880-1886, so where even my great-grandparents would have attended services), and led me to the best view of the river Prut in town.

While we were standing above the river Prut, through broken English and Ukrainian as well as some use of Google Translate, Petya told me about a friend of his in Sniatyn, Taras. His friend shared my surname and, according to Petya, looked a lot like me. The next couple of hours were a confusing whirlwind as Petya tried to contact Taras through various phone calls and finish our tour of Sniatyn, which included meeting his friends and touring another tiny exhibit run a local metalworker. Petya was eventually able to track down Taras and immediately led me to his motorcycle so that I could meet my newfound relative at a local café.

After a short motorcycle ride, I met Taras and his father. Neither spoke English, and my Ukrainian is still quite primitive, so I spoke with Taras over Google Translate at first. Even without efficient translation, it was already an emotional introduction; his father hugged me and looked at me with an astonishment that can’t easily be described, and Taras was brimming with questions that couldn’t be answered quickly. My branch of the family never contacted the relatives who remained in Ukraine after the war. My grandma and great-grandmother may not have known how or just wanted to move on from their traumatic losses, and no one living in my family speaks Ukrainian. To the family that stayed, we were a dark spot in the family tree. It is, of course, not lost on me that I am a long-lost member of the family who suddenly returned to visit at a very distressing time in Ukraine. From my position, I can never be certain, but I must imagine that the diaspora in these times is a very hopeful thing, as it ensures the survival of familial memory elsewhere. Even decades later, my WW2-wave diaspora family was still able to remember enough to allow this reconnection to happen.

After a while, Petya was able to find someone who spoke English more fluently, and she translated for us. Through her, I was able to briefly explain my part of the family history to Taras and his father. We exchanged contact information, and I sent them what family records I had so that we could begin mapping out our places in the family tree. I suspect that his branch is from one of my great-grandfather Yosyp’s brothers, but records regarding sibling ties are slim, so we may not know for sure, at least for some years to come. Our time there was limited, as Taras had work and I had a bus to catch back to Kolomyia. But I left Sniatyn knowing that, beyond my initial cautious hopes, our family had miraculously been reunited for the first time since WW2. This, as you might imagine, comes with a heavy emotion that is difficult to explain beyond pure astonishment. Taras and I are still in contact, and I am hoping to visit that branch of my family again in Ukraine someday (hopefully this time with better Ukrainian skills or a translator already on hand!).

My immense gratitude goes to Petya Kireev and his dedication in tracking down Taras on such short notice. It’s still so unbelievable to think of how my trip to the local ethnographic exhibit to see the textiles led to my reconnecting with my relatives. If it wasn’t for Petya’s generosity and energy that day, that rekindling of familial ties would have likely never happened.

So, out of all my experiences during my fieldwork trip to Ukraine, my time in Sniatyn was, by far, the most significant and emotional. This experience was the crowning jewel of my entire project.

Kosiv

My last day trip while in Ukraine was to Kosiv, which is another well-known heritage crafts center in Western Ukraine. Part of this fame is thanks to their long-standing weaving tradition, another part from their historical Saturday market (the largest textile market in Western Ukraine), but Kosiv’s greatest claim to international recognition is their painted ceramics tradition, which has even been inscribed by UNESCO as an intangible cultural tradition. And indeed, I did see a lot of Kosiv pottery while in the Ivano-Frankivsk oblast and even got to take some of it home with me! My visit was in regard to that first part, however – the Kosiv weaving tradition. With help from the staff from the National Museum in Kolomyia, I was able to schedule a visit to Kosiv in order to meet with a local Kosiv folk weaver, Bohdana. On one of my final days in Ukraine, I met with Bohdana at 9 and took leave of her at around 18:45. It was an incredibly informative trip, and she did a perfect job introducing me to Kosiv and its textile culture.

Once I reached Kosiv, Bohdana showed me to Gonchar Café, a popular local café that doubled as a ceramics studio and gallery of Kosiv painted ceramics. There, Bohdana introduced herself more fully: she had learned to weave on multiple different looms in university and was now continuing to develop her weaving at the Kosiv Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts of Lviv National Academy of Arts. She also worked as a professional weaver at Gushka Studio, which specializes in folk-inspired textiles. During this initial meeting, she showed me a PowerPoint of her tapestry designs and explained to me how she has been working on designing her own modern versions of historic Ukrainian woven tapestries. The designs she showed me were clearly inspired by different patterns and colors from Kosiv tradition, but had been expertly reworked with more recent trends in aesthetics. Bohdana planned to continue working with these designs during her studies.

After telling me about her previous work and her plans for her future tapestries, Bohdana took me to the aforementioned Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts. While here, I was able to tour the small student museum, where previously finished crafts by the students were on display, including woven tapestries. We then visited the embroidery department, where I had the privilege of meeting Nina Stef’yuk, a renowned expert who wrote the definitive book on Ukrainian embroidery. Stef’yuk was exceedingly kind, welcomed me to her department as a fellow embroiderer (she was very pleased when Bohdana showed her photos of my previous embroidery work), and gave me a tour of the space. While touring the embroidery department with Stef’yuk, I was able to see student-made samples of regional folk embroidery, experiments in applying historic embroidery to modern clothing designs, and altogether new fashion designs. These were presented in illustrations, small swatches of embroidery techniques and patterns, and full shirts and vests. At the end of her time with us, Stef’yuk let me pick a student-made motanka doll (shown in the photo) to take with me as a memento from my visit, which was very kind. Being able to meet such an expert Ukrainian embroiderer was by far one of the most memorable highlights from my fieldwork.

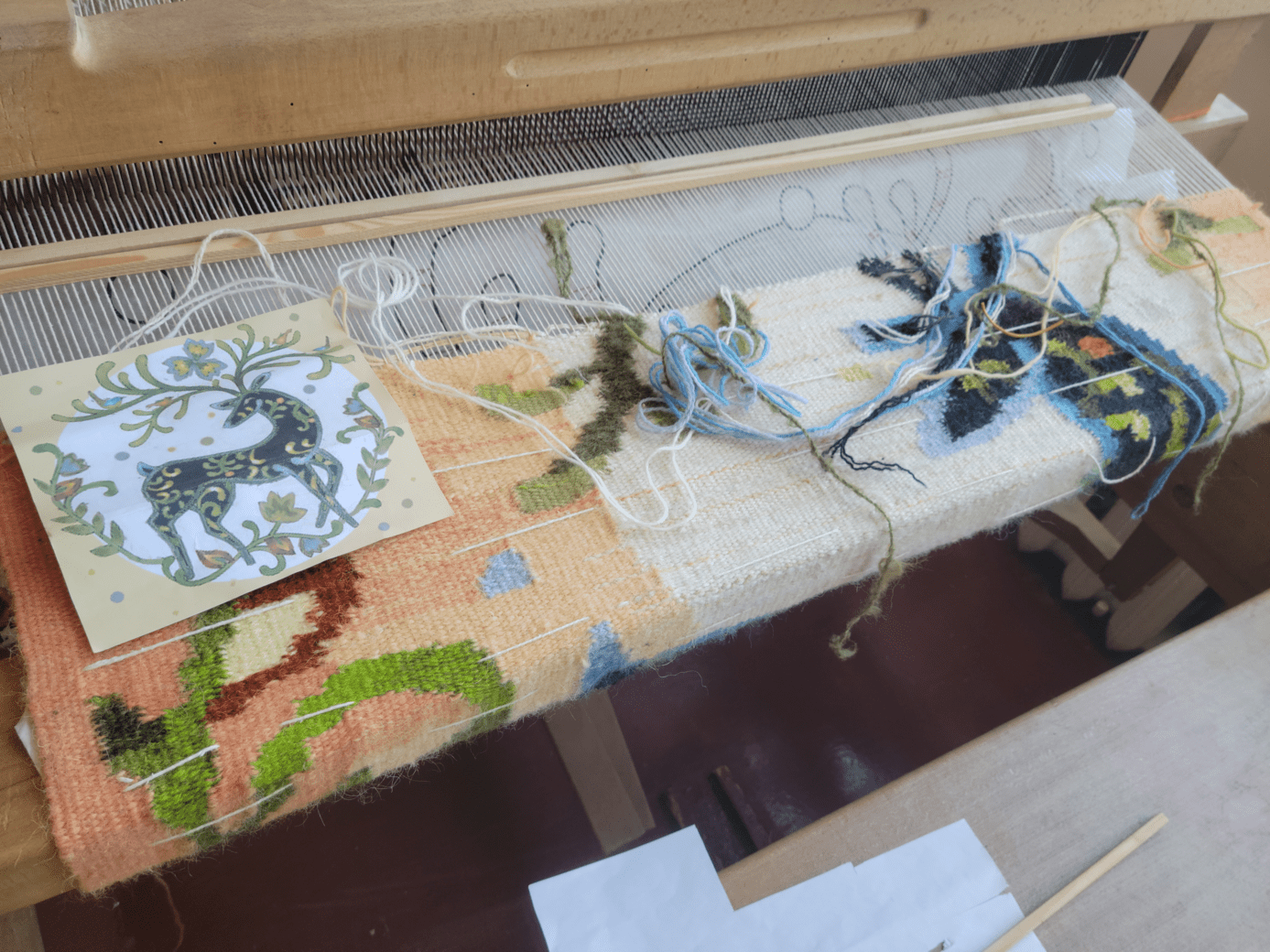

After touring the embroidery department, Bohdana led me to the university library, where I was able to look through and photograph several Ukrainian embroidery books. Some of the books I got to look through are very difficult to find for sale even in Ukraine, so getting to photograph the different books was very useful. I referenced a couple of these books throughout this project, and I will likely return to the rest over time as I continue to embroider. After the library, we toured the weaving department, filled with floor looms – this was a bit more out of my depth, of course. But during my time in these workshops, I was able to see so many beautiful tapestry designs that were clearly folk-inspired designs personalized to fit the weavers’ visions, some of which were still being woven at the time (such as the deer design). This was also my first time seeing how Kosiv weavers weave on their floor looms for myself; the lack of a shuttle, for example, was notable.

After touring the student workshops, Bohdana and I visited her place of work, the aforementioned Gushka traditional weaving studio. Gushka specializes in handmade folk-based designs, with a focus on clothing items, blankets (properly called lizhnyk), rugs, and other home furnishings. At the time of my visit, Bohdana told me that the studio had just completed a large order of pillowcases for a hotel in Canada, and they clearly have an international customer base. As we toured the workshop, Bohdana explained the process to me.

Their designs use the thicker wool fabrics so common in southern Pokuttia and among the Hutsuls, which require special preparation. Yarn for this workshop is provided by older women in the surrounding region. They get the wool from the local sheep in the Carpathian Mountains, sort it, wash it twice in the local streams, card the fleece, then finely spin the warp yarn and thickly spin the weft yarn. Once the yarn is prepared, it’s woven by hand (without a shuttle) on the workshop’s two-shaft looms. This was a condensed version, but this post goes into depth about the wool processing and weaving traditions around the Kosiv region. The fabric is then prepared, if needed, and shipped out. While touring the studio, I was able to feel the woven fabric (it really is very dense) and try on one of their woolen vests, which was very cool!

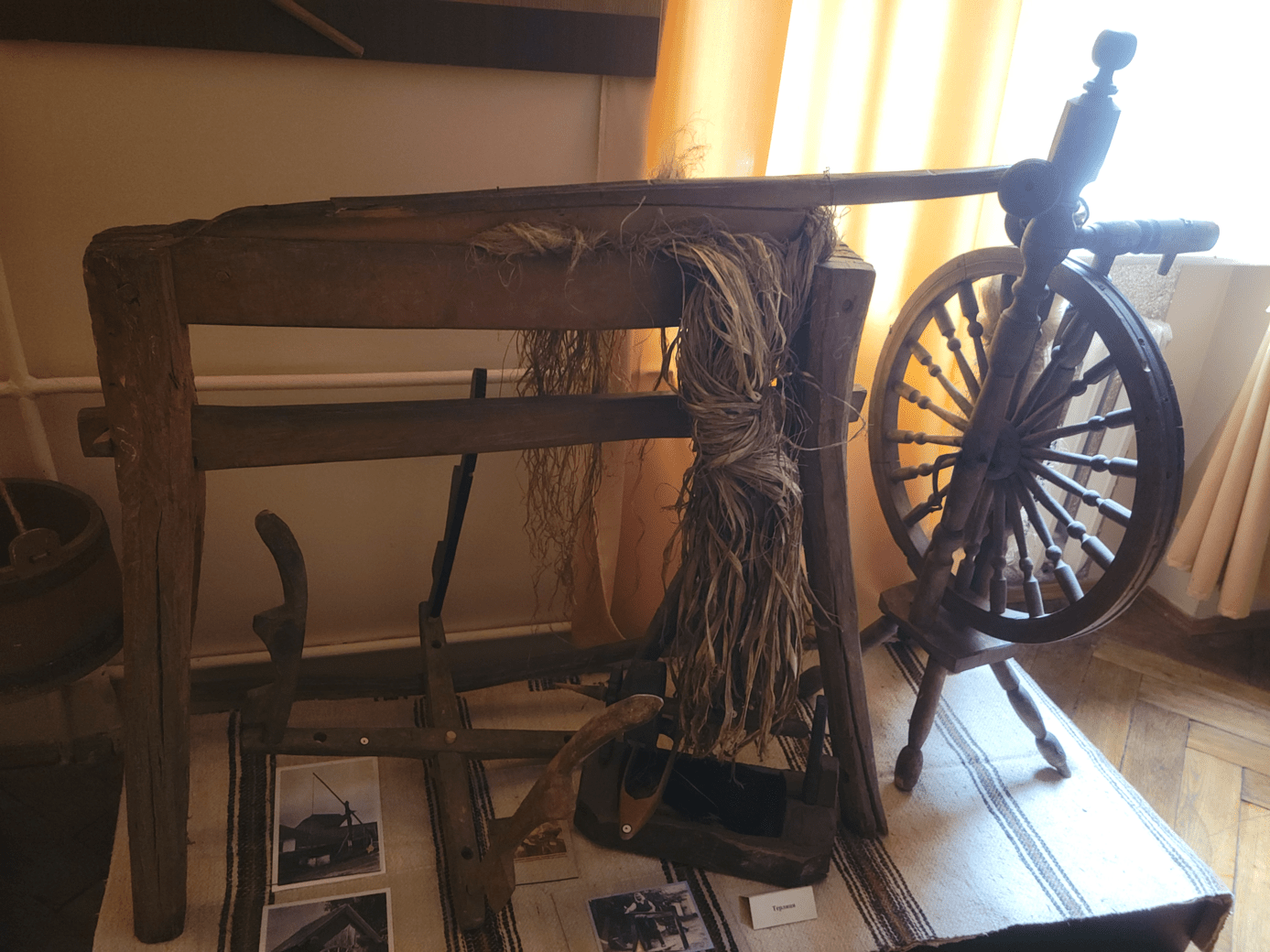

Our final stop was at the Museum of Hutsul Folk Art and Way of Life, which holds one of the largest public collections of Kosiv textiles and other handicrafts. Thanks to Bohdana, we were able to secure a guided tour of the museum, which Bohdana kindly translated for me. The museum consists of two rooms filled with the local textiles (including folk dresses, coverlets, lizhnyk blankets, and rushnyky) and their tools (including an old two-shaft loom, spinning wheels, combs for carding wool, etc.) as well as one room dedicated to the Kosiv painted ceramics. The painted ceramics room presented the history of the tradition – this can also be read about here.

Of course, I was more interested in the textiles. Kosiv, like Sniatyn, has heavily embroidered sleeves in red and black, though there are some marked differences. Kosiv, for example, has a type of sleeve that densely combines blue and red together to make the sleeve look purple from afar. Their embroidery also includes animals, and their opynka has horizontal stripes (like the Hutsul) instead of vertical stripes (like elsewhere in Pokuttia and Bukovyna). So, it was definitely interesting to go through and mark the similarities and differences. One last benefit from the trip to this museum was that I could touch a couple of the rushnyky on display, which allowed me to see the back of their embroidery.

After the museum visit, Bohdana then took me to visit her own home. On the walk there, she told me about her life since the war began. She told me how her life had been a bit up in the air between covid and the invasion, and she wasn’t sure about her next move. She told me about a foreign friend of hers who left not long after the invasion began, and she has had little opportunity to practice English since then. She told me how grateful she was to the Ukrainian armed forces for allowing us to even meet that day. And she told me how important it was to her that I left Ukraine with a good impression, because she wanted the outside world to know that Ukrainians were good people who didn’t deserve the troubles of the current war.

At her home, Bohdana showed me around her family’s garden and house. She showed me the kalyna berries that grew in the garden, and I got to taste them for the first time in my life. For dinner, her mom cooked us banosh, which is cornmeal seasoned with sheep cheese. To Bohdana, it was important that I not only look at the textiles, but also experience other parts of Kosiv culture (something that I wholeheartedly agree with!). After dinner, Bohdana showed me her previous woven works, then taught me how to weave on her tapestry loom – which I’ve written about in the third section of this site.

Bohdana walked with me to the bus station so that I could take the last bus back to Kolomyia. The day she had planned was so intense but so fruitful and unforgettable. I truly appreciate Bohdana for having spent a whole day introducing me to Kosiv culture and weaving tradition, and for taking me into her own home. It was an incredible experience that has enriched my entire relationship with Ukraine (as well as this project), and has made me want to return when I can.

Even still, she reiterated one last time how much she hoped I was having a pleasant time in Ukraine, and how she hoped that foreigners would not forget the war in Ukraine. It was, after all, the brave efforts of the armed forces that even allowed my fieldwork trip to happen, which I did not forget for a single day during my visit and since then. This is a noble reminder, of course, so I will end Bohdana’s section and this page with a resource on how the reader might help Ukraine during this war.