Vyshyvanka

The vyshyvanka (or historically, the longer sorochka) is the true centerpiece of the Sniatyn folk dress. The shirt is where the embroidery is showcased, and the embroidery is an immensely influential factor and characteristic of the folk dress. In the modern context, the vyshyvanka is undoubtedly the most well-known and celebrated component of historic Ukrainian folk clothing.

Since the vyshyvanka has been extensively explored by many, many others, I will not be going in-depth with the history and meaning of the vyshyvanka here, as I did with the other components of my dress. For a basic introduction to the vyshyvanka, I encourage readers to check out this article from the Kyiv Independent or even simpler articles like this one. For further information on the current significance of the vyshyvanka in the context of the war, articles like this one are very insightful. And research on how wearing the vyshyvanka contributes to building Ukrainian identity has been written about here and here. There is indeed much to say about the vyshyvanka being a part of the nation’s genetic code and a type of spiritual armor for Ukrainians, and I encourage the reader to look to these sources for the full context of the vyshyvanka’s significance for Ukrainian culture, identity, and even spirituality.

Finally, for those who are looking to learn to embroider in the historical Ukrainian style, complete with the intangible traditions, I recommend checking out the posts on this blog, as the writer is an actual teacher of historic Ukrainian embroidery stitches and patterns.

For those particularly interested in why I chose to craft a vyshyvanka in place of the sorochka and how I designed my embroidery, I recommend first reading my Design page. To be brief, I chose to craft a vyshyvanka so that I could wear my embroidered shirt in a variety of contexts in the modern day. As for the embroidery, I referenced historical patterns that were used on Sniatyn shirts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I then arranged and adjusted those patterns to follow the traditional red & black embroidered sleeves and my own preferences.

Instead of going too much in depth, this page will briefly recount the actual process of embroidering and crafting my vyshyvanka. The final photos, however, will most likely be the star of this page.

Intangible Inheritance

I’ve been embroidering as my main craft for quite a while – over a decade (which seems like a fair chunk of time at the age of 27).

My mom was my teacher. She had embroidered for years, having learned the skill at home as well as during her career as a costume seamstress. Over the years, she had mastered most of the basic stitches, including the ones that I needed for my vyshyvanka. Despite the many stresses of life that came with being a single mother, my mom always found happiness in crafting and wanted to share it with me in her few free moments. She had explained to me time and time again how needlework was meditative for her, that she approached it calmly and with a measure of happiness, and that she always embedded herself in her work. I couldn’t doubt her claims either; my mom has always gotten into such a good mood when crafting. In an otherwise tumultuous life, needlework was always my mom’s pride and joy. And when she taught me how to embroider, she imparted this knowledge to me.

Her mother had practiced needlework in the exact same way, using it as a form of calm meditation, and she passed this tradition on to her willing descendants. Of course, my mom directly taught me how to embroider, so my knowledge and memories of embroidering are tied to her.

My mom and I are certainly not the only ones who approach embroidering in this way. In Ukrainian intangible tradition, embroiderers should ideally embroider when they are calm and in a good mood. Practically, this makes sense; embroidering when you’re angry/etc. leads to unwanted mistakes, whereas embroidering when you’re in a good mood improves the quality of the embroidery. But there is also a nicer symbolic reasoning to this. When a Ukrainian embroiders, they are embroidering their best intentions as well as protection for the wearer and their future. A lot of this is conveyed in when and how one embroiders. For example, a woman should generally not embroider when sick or upset. By approaching embroidering calmly and with good thoughts, the embroiderer works their best intentions into the embroidery and secures the future protection and happiness of the wearer.

In the Sniatyn-specific tradition, when an embroiderer crafts a shirt for herself, she is silent while working so as to focus her energy into the embroidery. When embroidering a shirt for a loved one, she should pray before embroidering so that only her best energy and thoughts are worked into the embroidery. In this way, some forms of spirituality may be found within the intangible tradition. It is understandable that Ukrainian embroidering has been defined as a “ritual of self-expression” and “a prayer without words,” wherein the embroiderer expresses her thoughts, personality, spirituality, and good-willed intentions through the act of embroidering.

A few other traditions are carried in the skill of embroidering. A common tradition is to never make knots in the thread, as knots carry negative energy and also make the back of the embroidery unduly bulky. Instead, Ukrainian embroiderers tuck the thread ends beneath their stitches. Another tradition is to make some “mistakes” in the embroidery; negative spirits / evil eye / etc. are attracted to perfect beauty, so it is best to make some mistakes in the embroidery in order to create imperfection. I have seen some embroidery, for example, suddenly switch colors where it shouldn’t in order to disrupt the pattern. The embroiderer may also make little embroidered marks inside the fabric in order to stave away evil spirits. And finally, even small amounts of embroidery are usually added around shirt openings (cuffs, collars, hems) in order to keep out evil spirits. There are some other intangible traditions as well, such as those outlined here, that might interest readers.

Adhering to these little practices and keeping up a good mood when embroidering ensures that the final embroidery will protect the wearer in the future. So, when approaching my own embroidering process for my vyshyvanka, I was careful to pay mind to these intangible traditions. I want the most protective vyshyvanka I can get, after all.

My Embroidering Process

I love the traditions associated with embroidering in Ukrainian culture. I think a lot of the practices are wise (such as avoiding knots), and I like the idea that my intentions during my embroidering process will protect me in the future. A lot of these practices are also what I was taught from the beginning by my mom, such as approaching needlework only when in a good mood. I tend to adhere to these practices whenever I embroider, even when following modern designs. I truly want my work to carry a bit of myself and my best intentions going forward.

Now, I can’t adhere to everything when embroidering. More specifically, I am not religious. My praying before embroidering would not really mean anything to me, so it doesn’t feel right to include it in my own process. Regardless, I still try to respect these traditions as much as I can. I keep my best intentions in mind when embroidering and embroider for a safe and happy future for the wearer (which, in this case, is me).

Sometimes following this tradition can, admittedly, be a bit of a burden. I am rather strict about not embroidering when I am sick or upset. I really don’t want to impart these memories of my being ill or angry or whatever into my work; I feel like it would ruin the entire process and final item for me. To embroider for a good future while experiencing a bad presence creates far too much internal dissonance. And this is all well and good for the most part… until I experience a rough few months while on a tight deadline, which I experienced for the first time during this project. A lot of my vyshyvanka was meant to be embroidered during the autumn of 2023, but instead I spent a few weeks stressed from moving apartments with my cats on a tight budget and then several more weeks trying and failing to recover from a horrible cold. Every time I was starting to feel good-spirited enough to embroider, something would happen to sour my mood, and then I didn’t feel right embroidering. It set me back at a time when the end of my MA program, and therefore the deadline for my vyshyvanka, was already looming. And while I still very much agree with and respect the intangible traditions for embroidering, they made for a logistical nightmare for this project.

But once I was in a more stable position, the embroidering went quickly. After many years of embroidering, I’m good at notching in stitches quickly and consistently. Once I had the patterns memorized, I was able to complete large swaths of the patterns within a matter of days. My designs for the shoulder insets are dense, which was daunting time-wise, but actually approaching the embroidery felt comfortable upon starting in earnest. And while embroidering, I made sure to follow the intangible customs; I kept my best intentions in mind, never made a knot in the embroidery, and made little “mistakes” that I would recognize to warn away negativity. I have done everything I can to impart protection and happiness to my vyshyvanka through the act of embroidering.

Like my mom before me, I now use needlework as a form of calming meditation. Luckily for me, I am very skilled at turning off my brain, so that I can embroider in a positive mood without overthinking or getting bored in the meantime. Much of my embroidering is done with little thought; going through the motions is quite calming for me. If I did spend time reflecting on anything while embroidering, well, see the 2nd section of this site for the outcome. Embroidering a vyshyvanka gives one a lot of time to think and reflect, and I spent much of my time embroidering reflecting on my heritage and how this crafting process strengthens my own Ukrainian identity.

It also didn’t take long for me to get irrevocably attached to my embroidery; there were definitely moments when I would get anxious about not getting to embroider, because that was all I wanted to do. Embroidering the vyshyvanka came to define my few moments of serenity and reprieve in an otherwise busy life. Threading the needle through that particular fabric in the particular pattern over and over and over again became my core muscle memory and the activity in which I was most comfortable. Embroidering is simply something that I do, like my Ukrainian foremothers. The more I worked on it, the more I understood how my mom and grandma could find so much peace and happiness in crafting amidst all the other worries they had to solve.

I can’t say how long the embroidering process took in total. It spanned several months, complete with pauses in between so that I never had to touch my embroidery while in a bad mood. I don’t doubt that embroidering alone took roughly 200-300 hours, though timing it past the first 150 hours became entirely too tedious. For the most part, I snuck embroidery in between my daily activities and during my free moments in the evening. On days when I could embroider with no worries about any other responsibilities, I would easily count up to 13 hours of embroidering.

Embroidering for my vyshyvanka took a lot of patience and dedication, but it also felt natural to do after so many years of embroidering. I’m really excited to have taken on such an intense process and finally embroidered my own vyshyvanka.

Construction

I won’t be getting too much into the construction here since sewing up the vyshyvanka has already been written about extensively. I referenced Kmit, Luciow, & Luciow’s book for the basic sizing and construction of my own vyshyvanka.

The steps involved are fairly basic. When sewing your own vyshyvanka, make sure to process your linen first before embroidering and sewing, as this ensures no further shrinkage when washing the fabric in the future. It’s also best to already be familiar with how to cut linen fabric properly, as its weave tends to be uneven. After that, it’s fairly easy to cut the fabric into the basic pattern, embroider the sleeves / cuffs / collar, and sew it up. The only real change I made to the pattern was to make my own cuffs shorter, as I have rather small wrists.

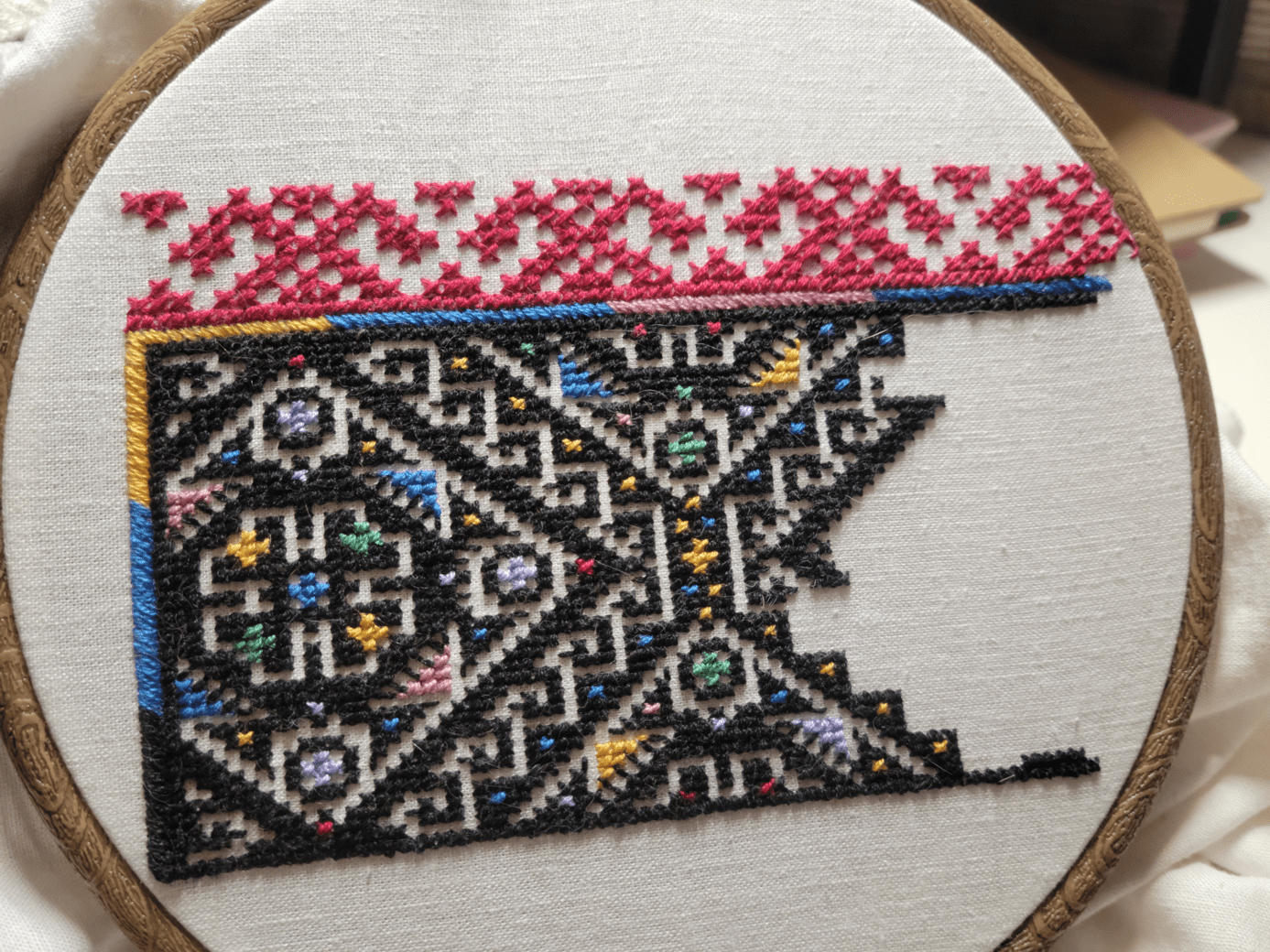

For the embroidery, I will note that my shoulder inserts are 12” (30.5 cm) wide and 6.5” (16.5 cm) tall. The embroidery for the cuffs is ~7” (17.75 cm) wide and ~1” (3 cm) tall.

Since I am basing my own vyshyvanka off of the older Sniatyn sorochka, I did make some changes to Kmit, Luciow, & Luciow’s more regionally-generalized pattern. This affected the collar in particular, as it meant sewing the top of the front and back fabric pieces into a drawstring collar, then cutting and hemming (in this case, with a blanket stitch) a deep V-neck with red thread. The string for the drawstring collar is made of woolen red threads that I braided for extra security. Some embroiderers add pompoms to these drawstring threads, but to be honest, they bother me a bit, and they’re quite modern-looking compared to the older shirts, so I decided to skip the pompons. A lot of older Sniatyn shirts also smock their sleeves at the end, but since I was using the preset pattern for the sleeves that made them narrower than needed for smocking, I just used normal gathers instead.

Final Words

And, well, that’s it! I now have my own Sniatyn-based vyshyvanka to wear to festivals!

More importantly, by embroidering my vyshyvanka, I have worked to mend the trauma in my family and strengthen my Ukrainian identity. Researching Sniatyn embroidery led me to Sniatyn itself (the first of my family to return!) and, miraculously, to reestablishing ties with our family that remained in Ukraine. This is already astonishing and an accomplishment of this project that I never dared to hope for.

Moreover, by designing and embroidering my own Sniatyn-based vyshyvanka, I have worked to restore my family’s intangible tradition of embroidering within its original Ukrainian context. In choosing traditional patterns, I have reconnected our surviving intangible inheritance (skills + built-in customs) and the memories tied to it to the proudly Ukrainian aesthetics and mode of self-expression of my foremothers. Through embroidering, I have taken the effort to dismantle my grandmother’s echoing shame and pain around her Ukrainian roots, and instead reclaim this culture and identity for my mother and me. The reflection undertaken throughout my embroidering process enhanced my understanding of my own family, culture, and identity. It also informed me of what this project really means for healing the leftover intergenerational trauma from my grandmother’s experiences with settler colonialism. I can help break this cycle of shame and silence about our own history and roots. When I embroider and wear my vyshyvanka, it builds a sense of joy in my Ukrainian culture and identity.

And at the end of this project, I can definitively say that crafting my folk dress (and especially embroidering the vyshyvanka) has accomplished what I set out to do. It has helped me reestablish the links to my Ukrainian heritage in several indescribable ways (though I have certainly tried my best on this blog). In embarking on this journey, I have worked to solidify and strengthen my Ukrainian identity, and my hand-embroidered vyshyvanka is the crowning symbol of this journey and its success so far.

Okay, now we can get to the photos! Here are the cuffs:

And the insets: